Folding Screens and Portraits

Veronica Stigger

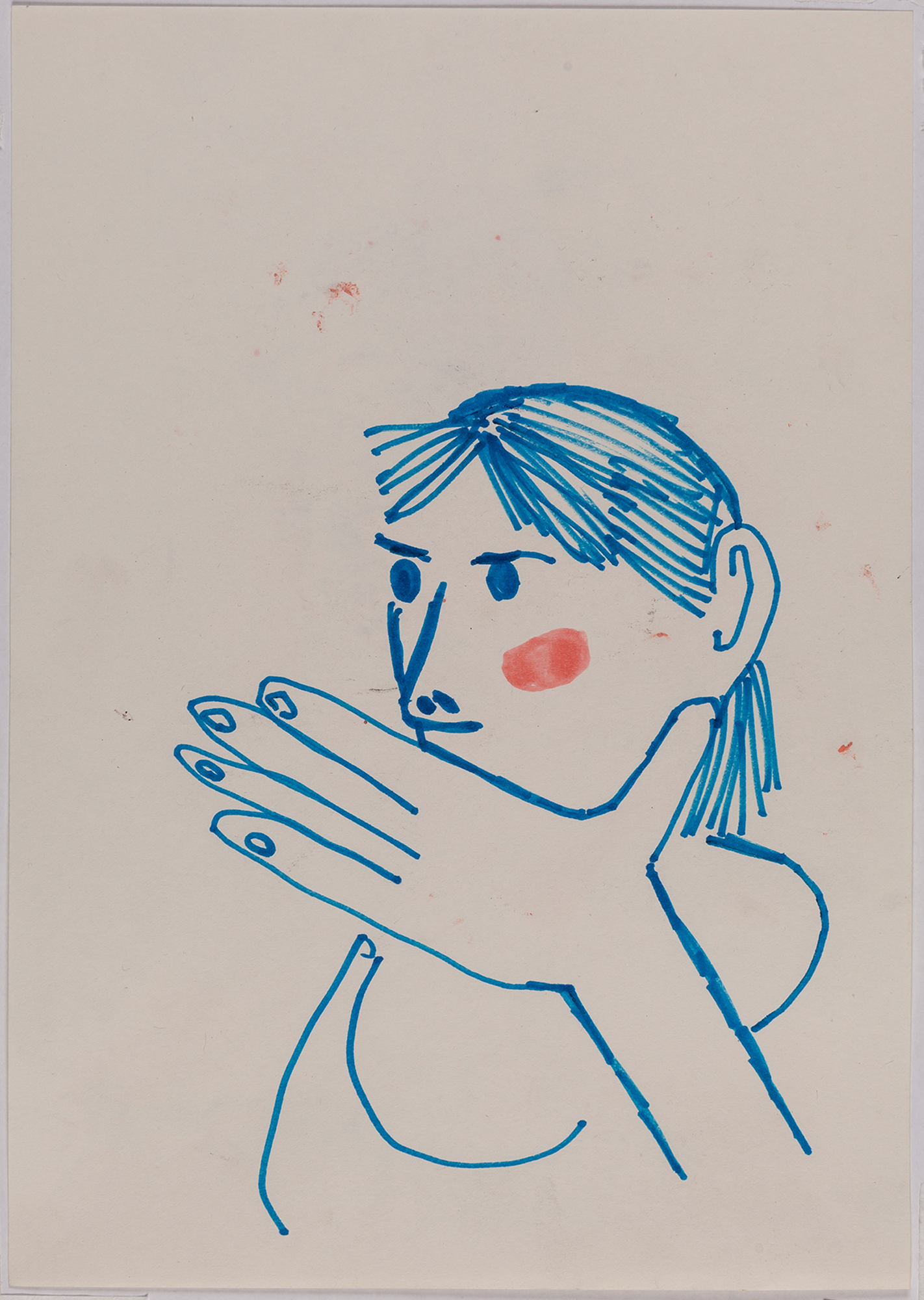

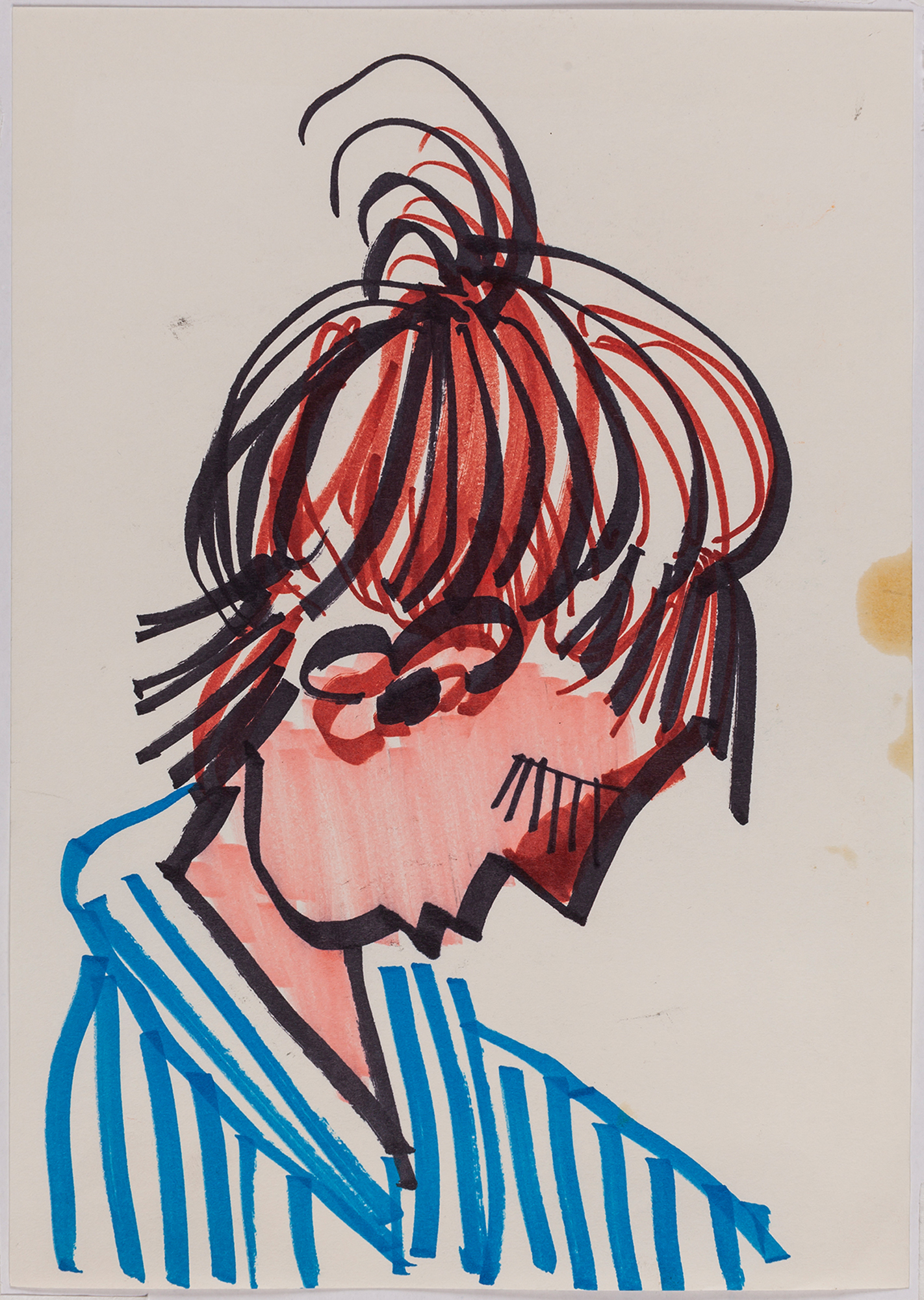

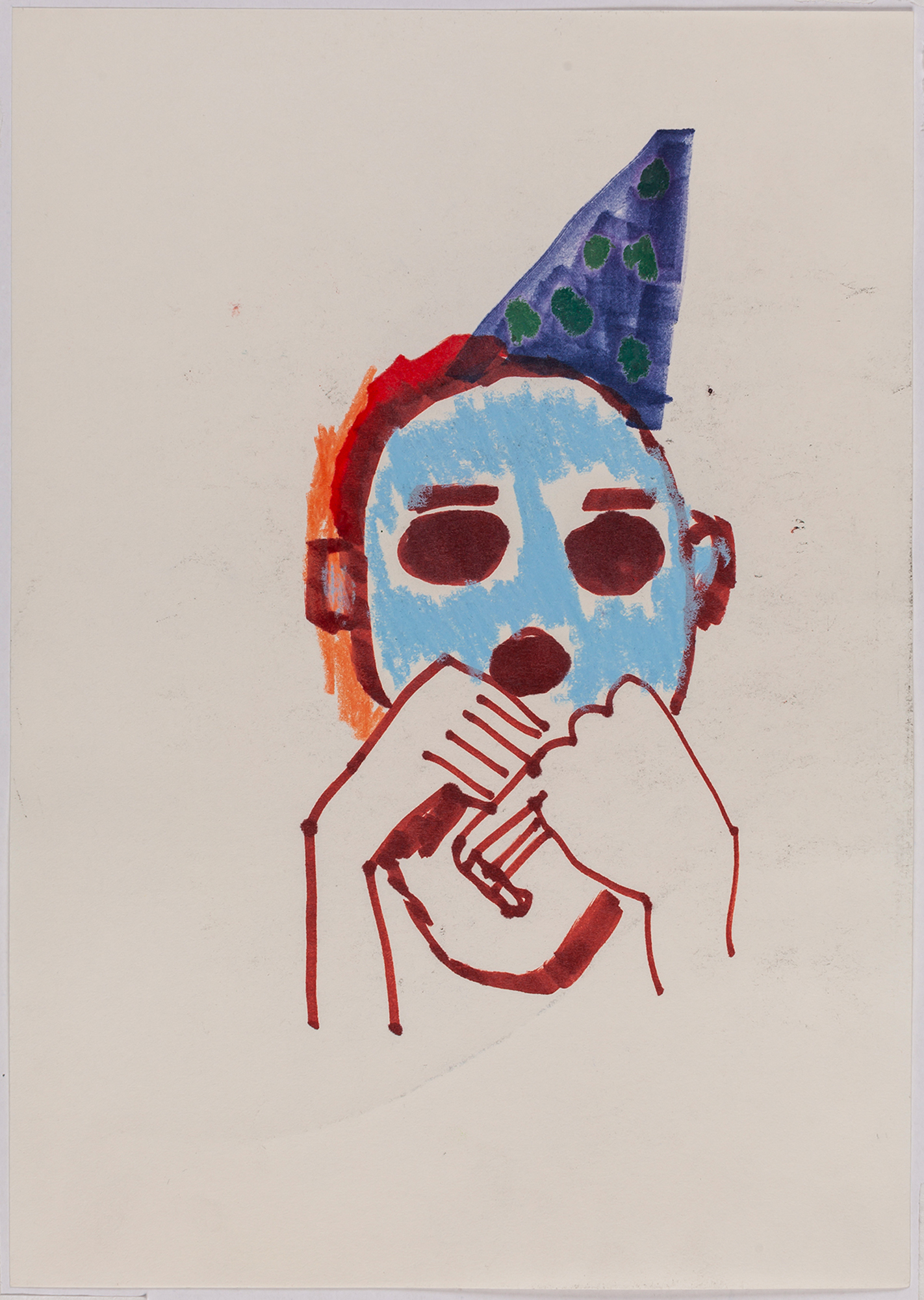

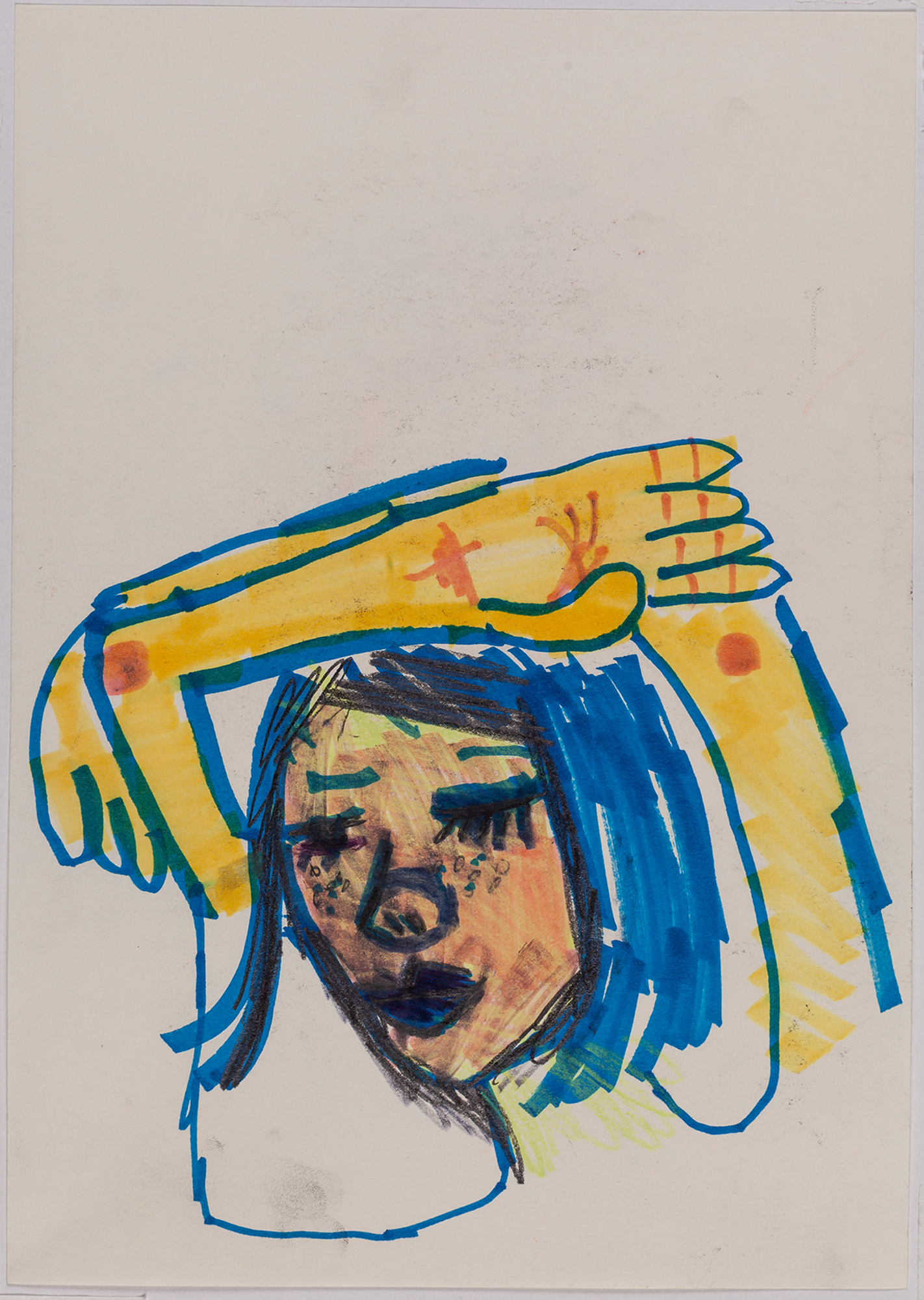

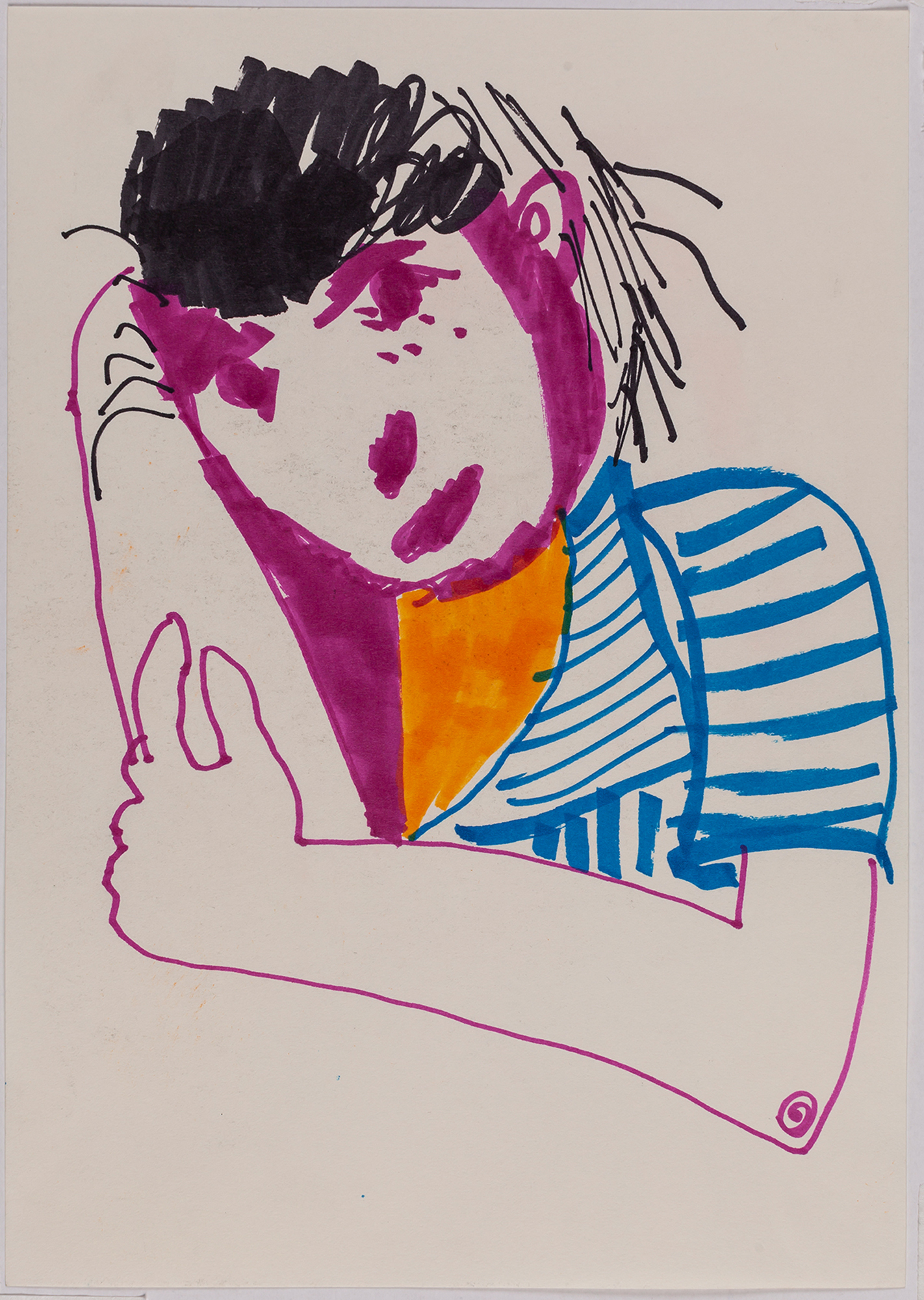

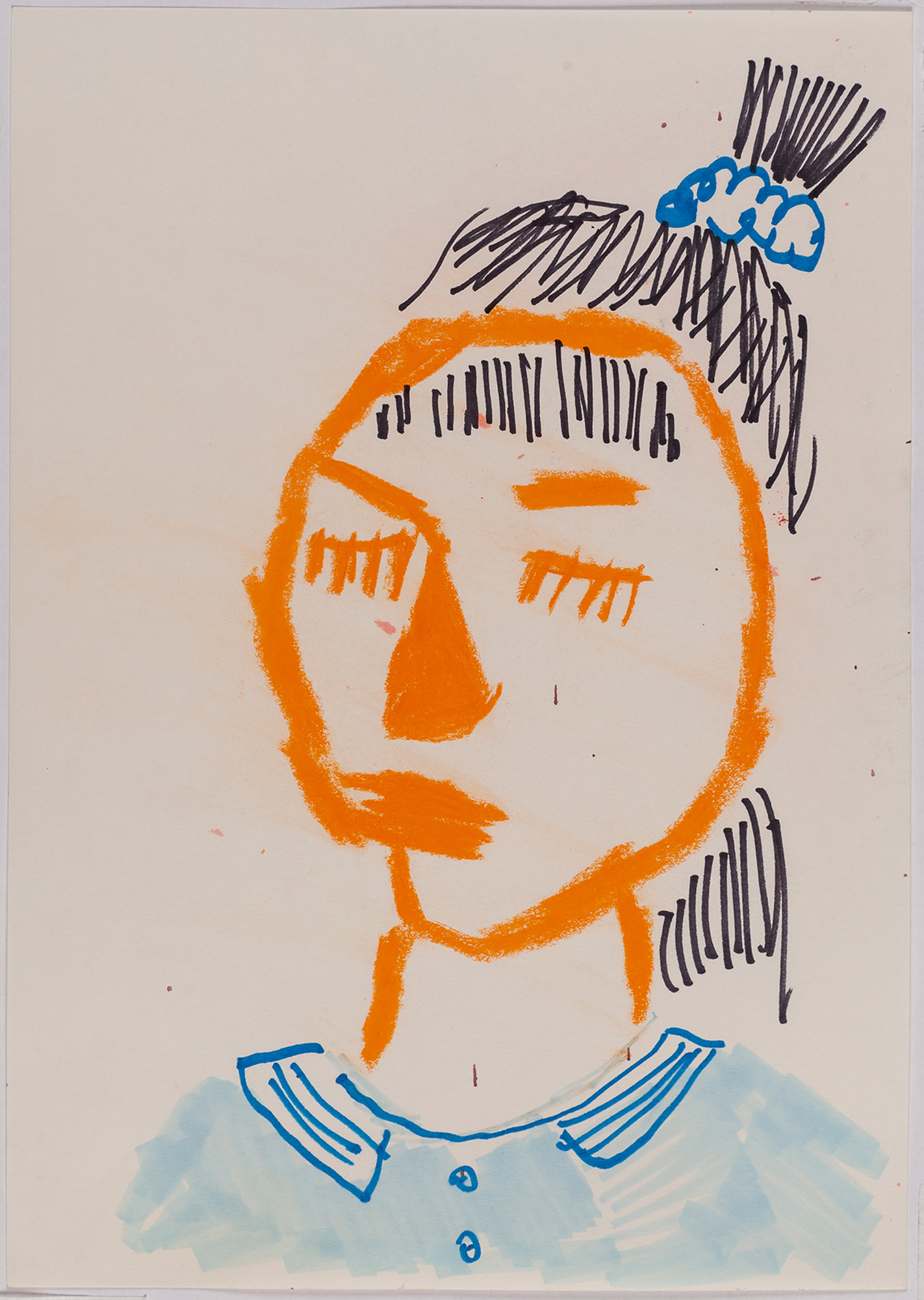

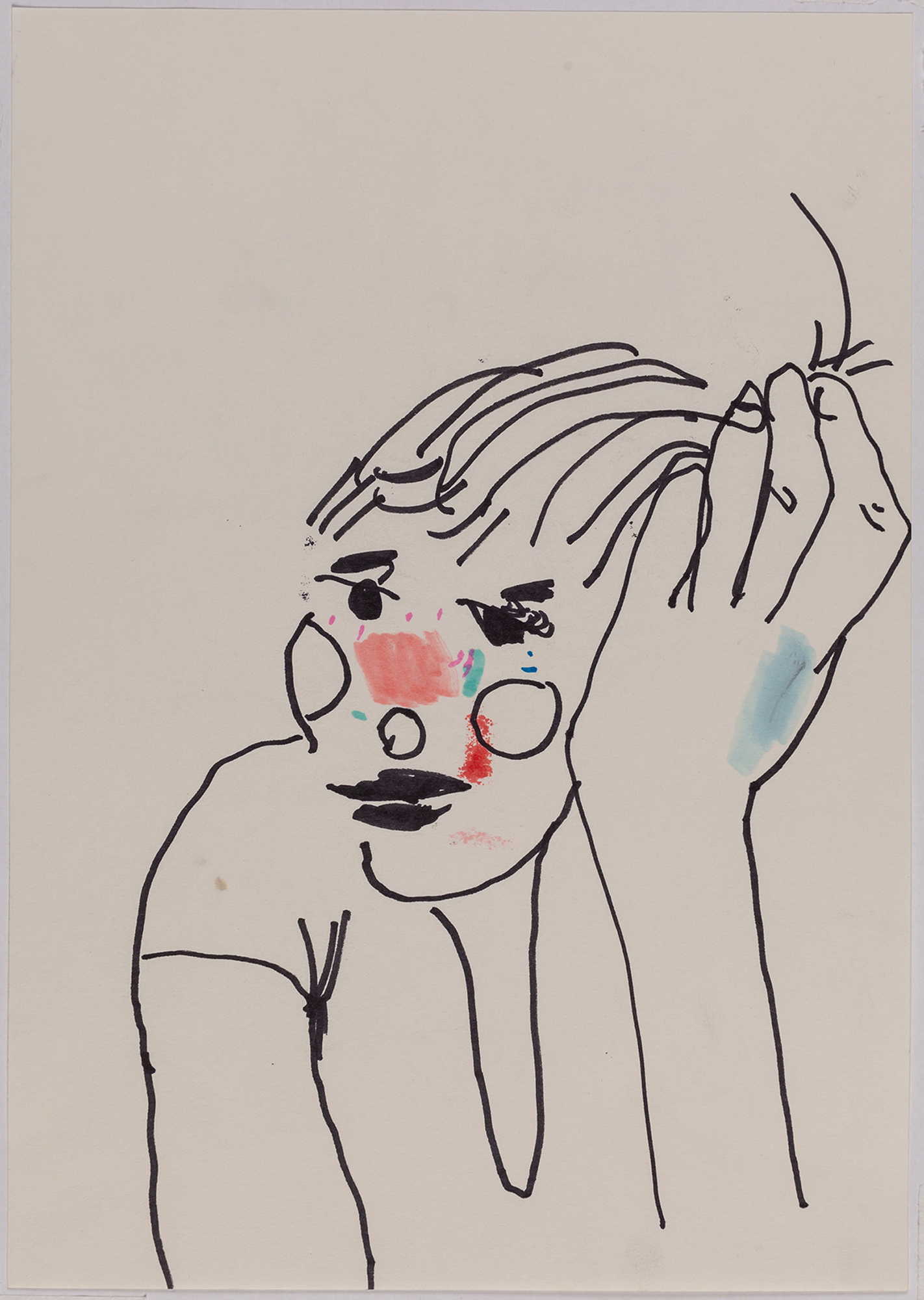

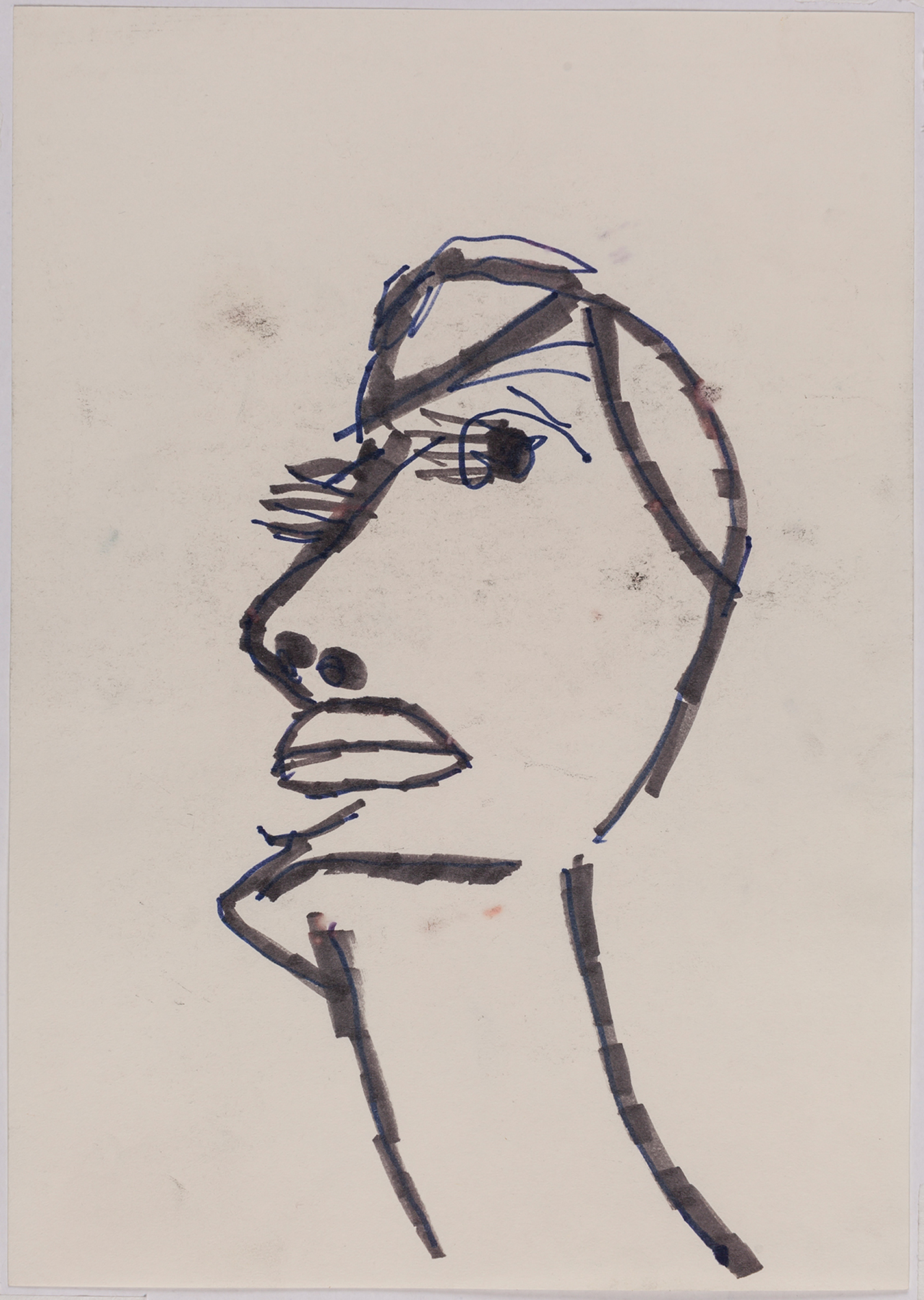

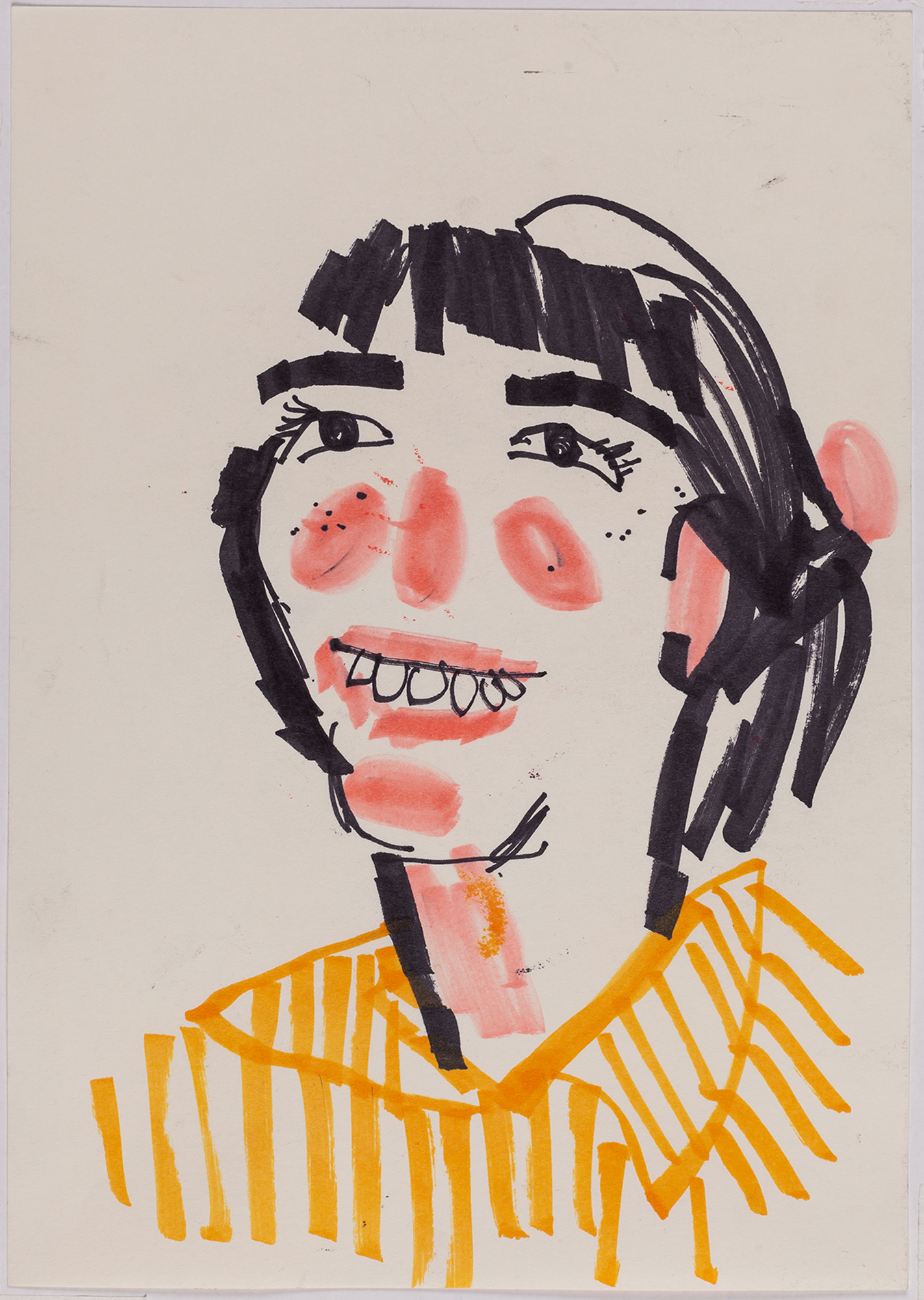

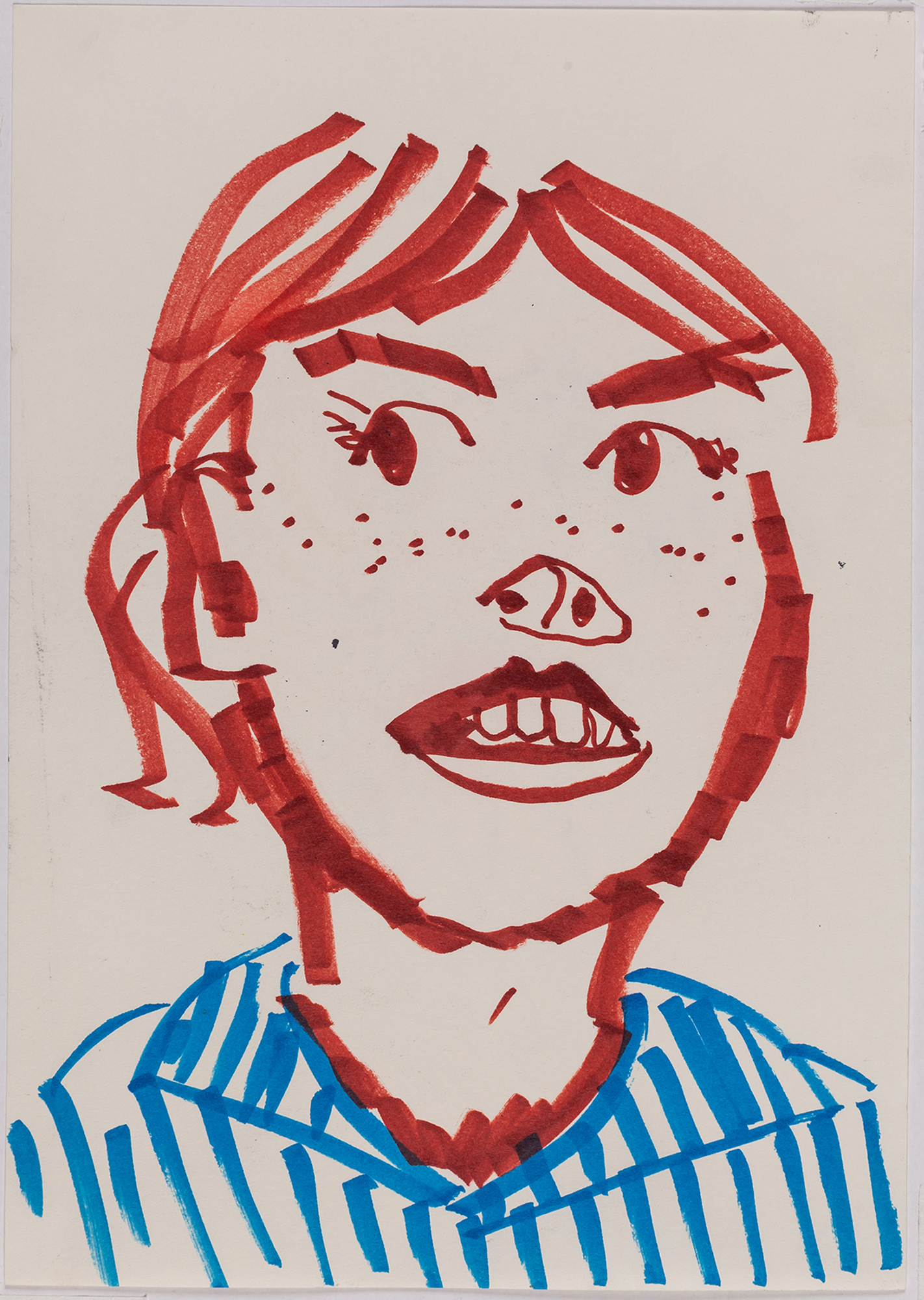

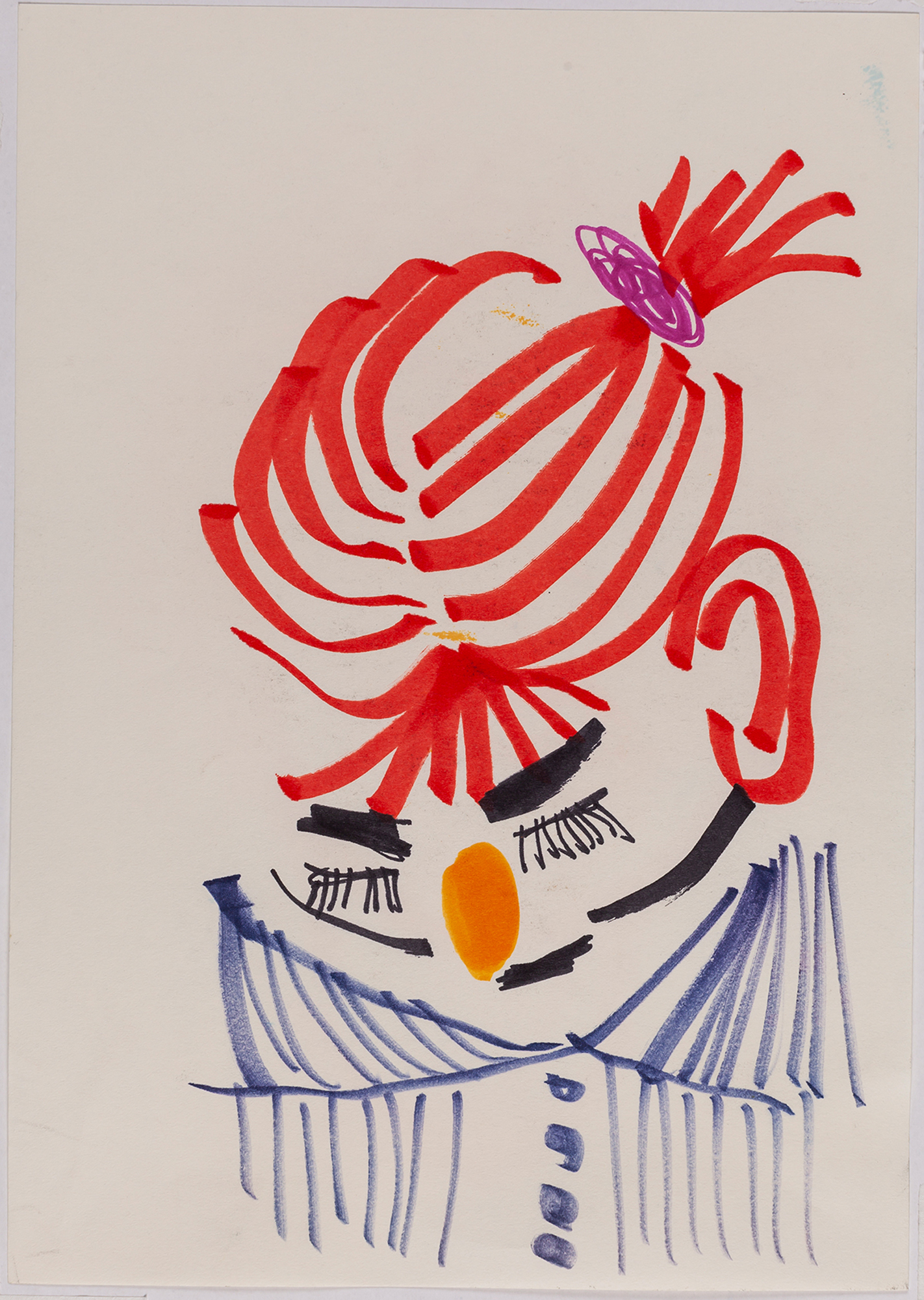

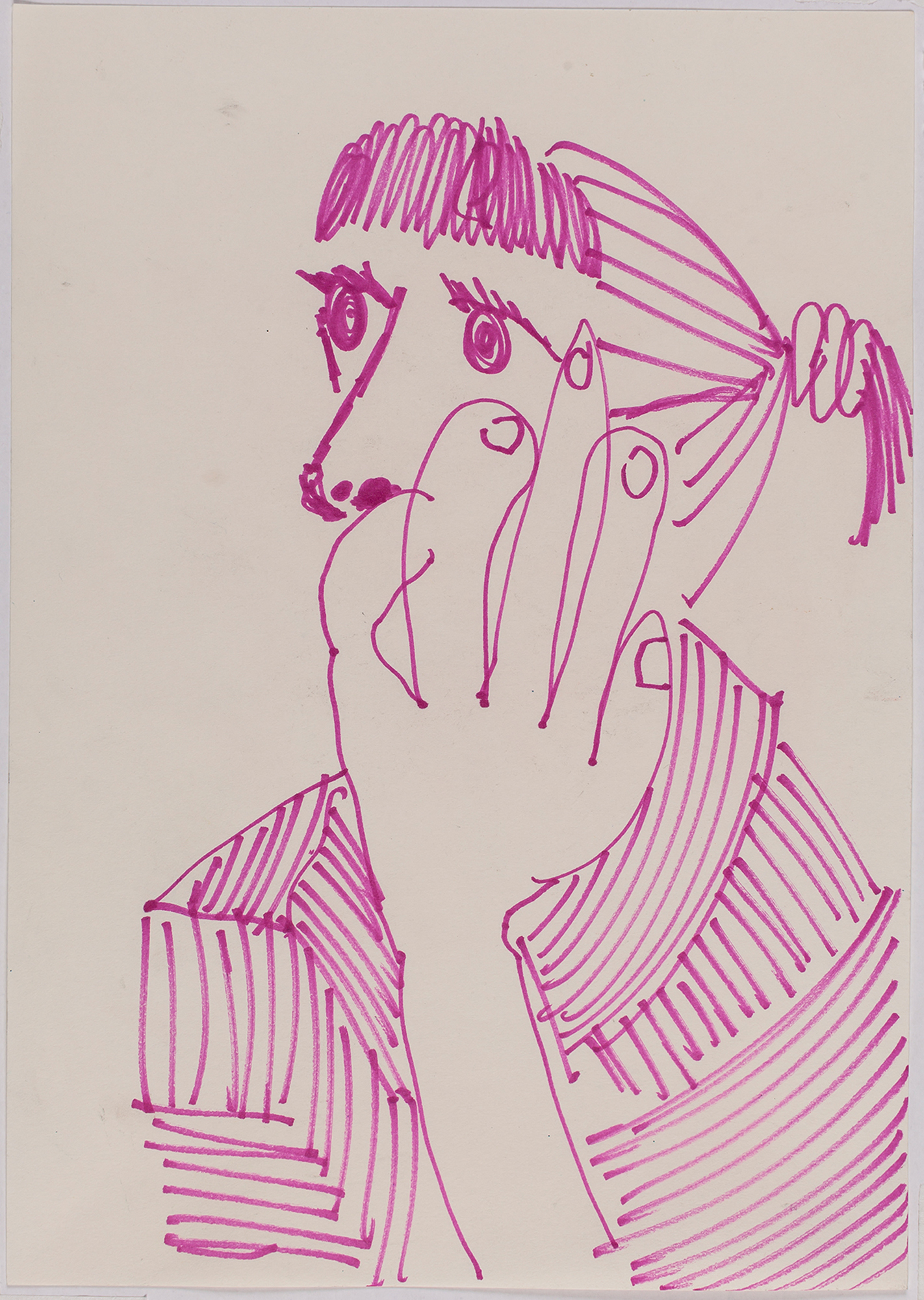

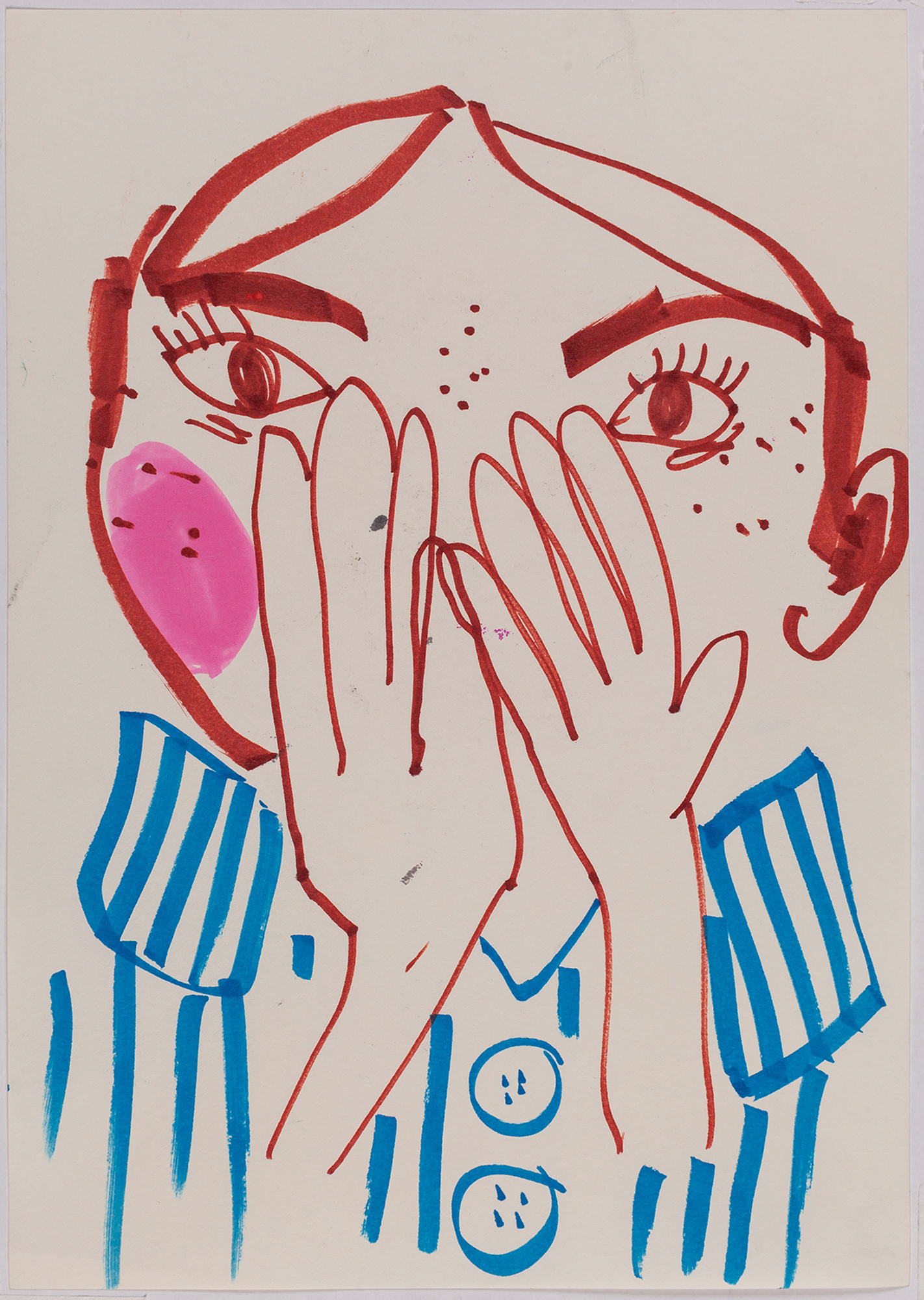

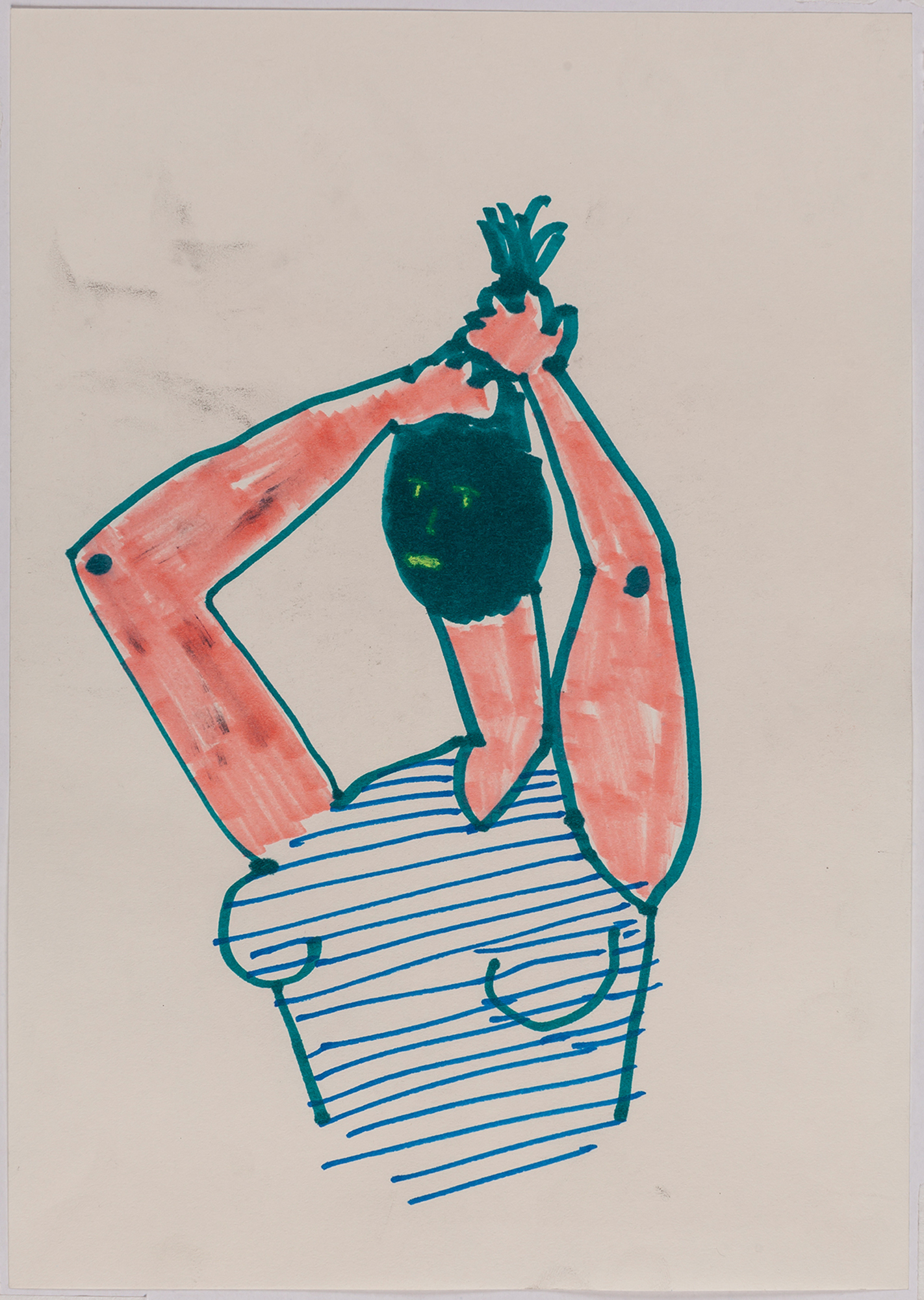

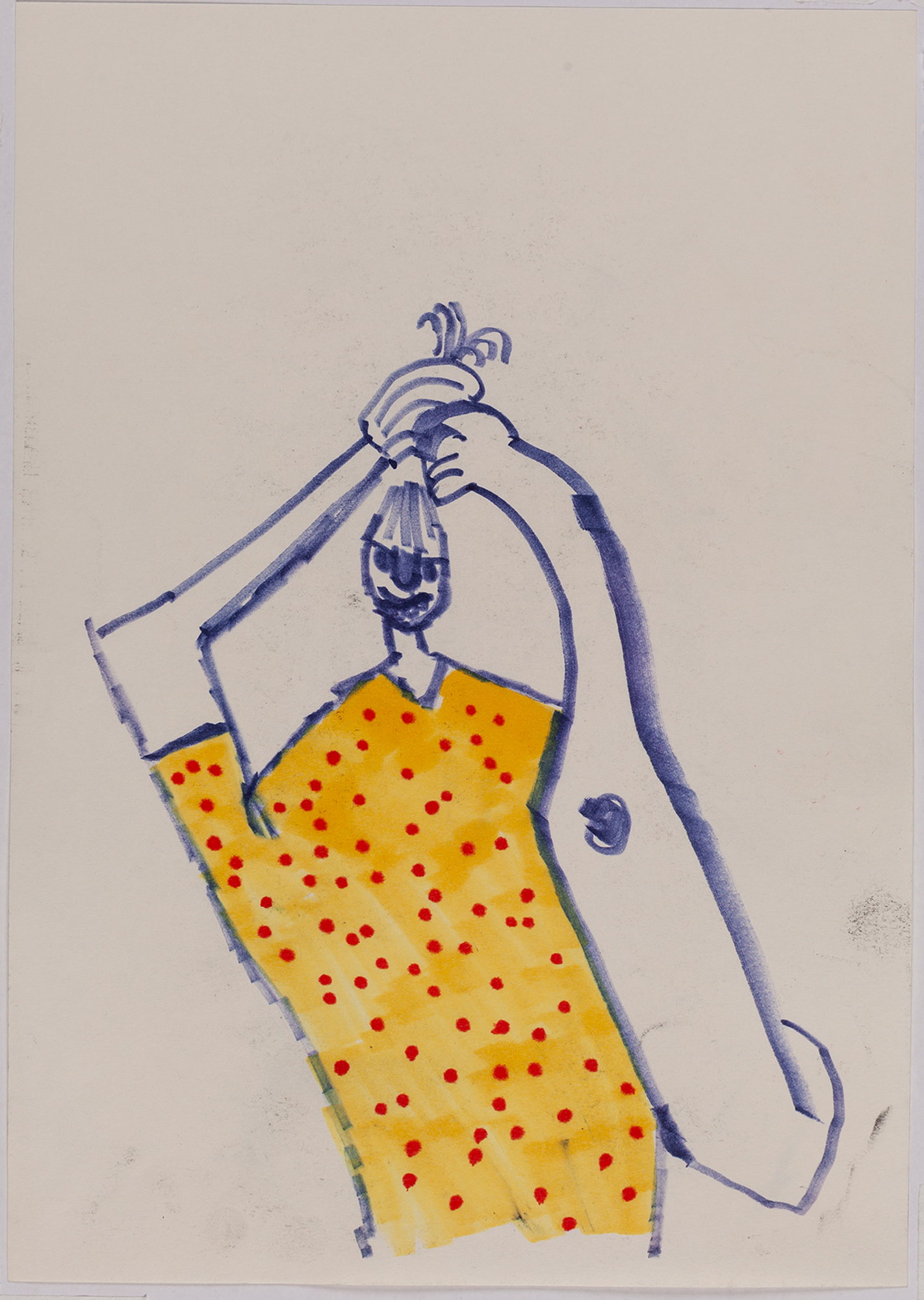

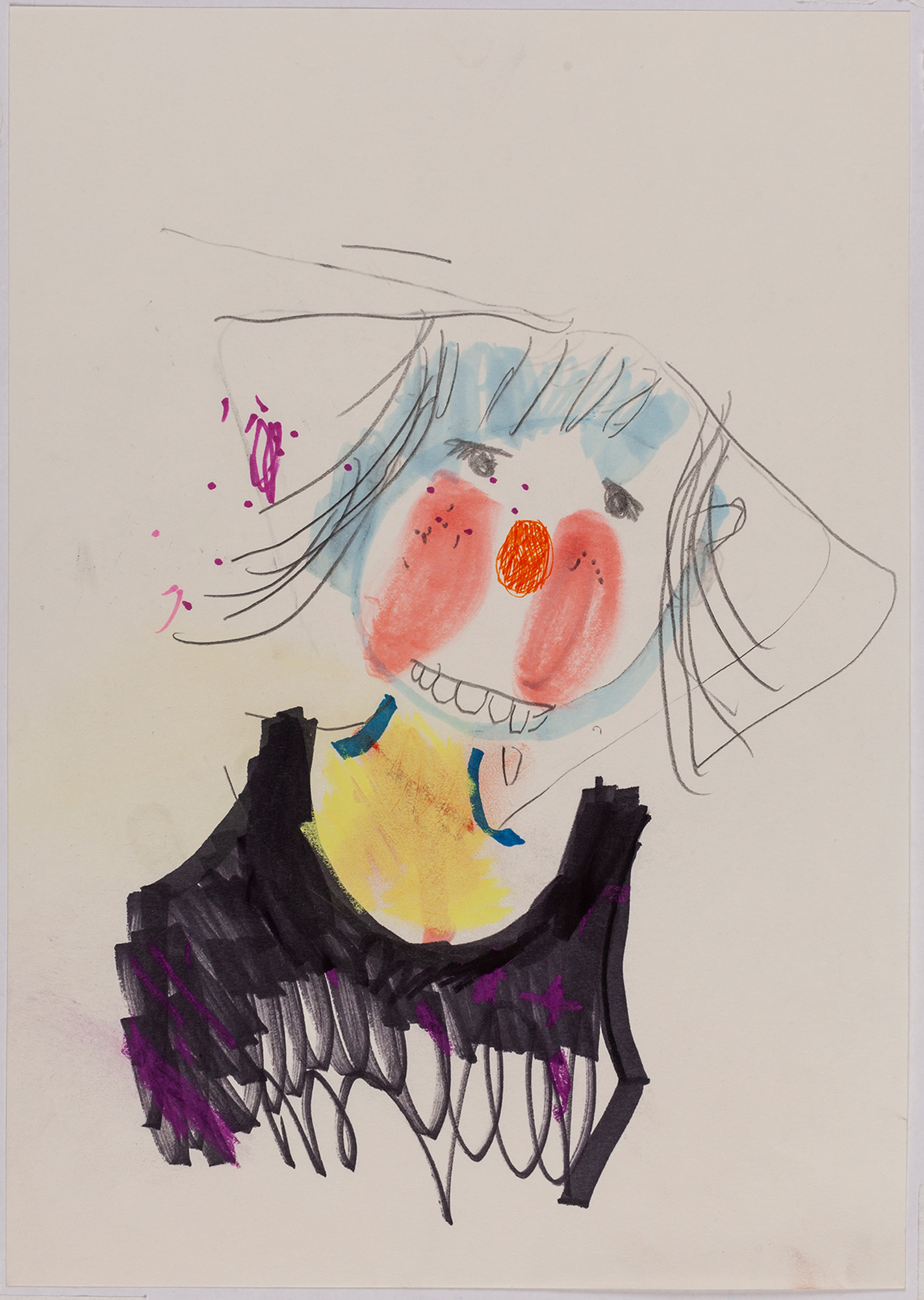

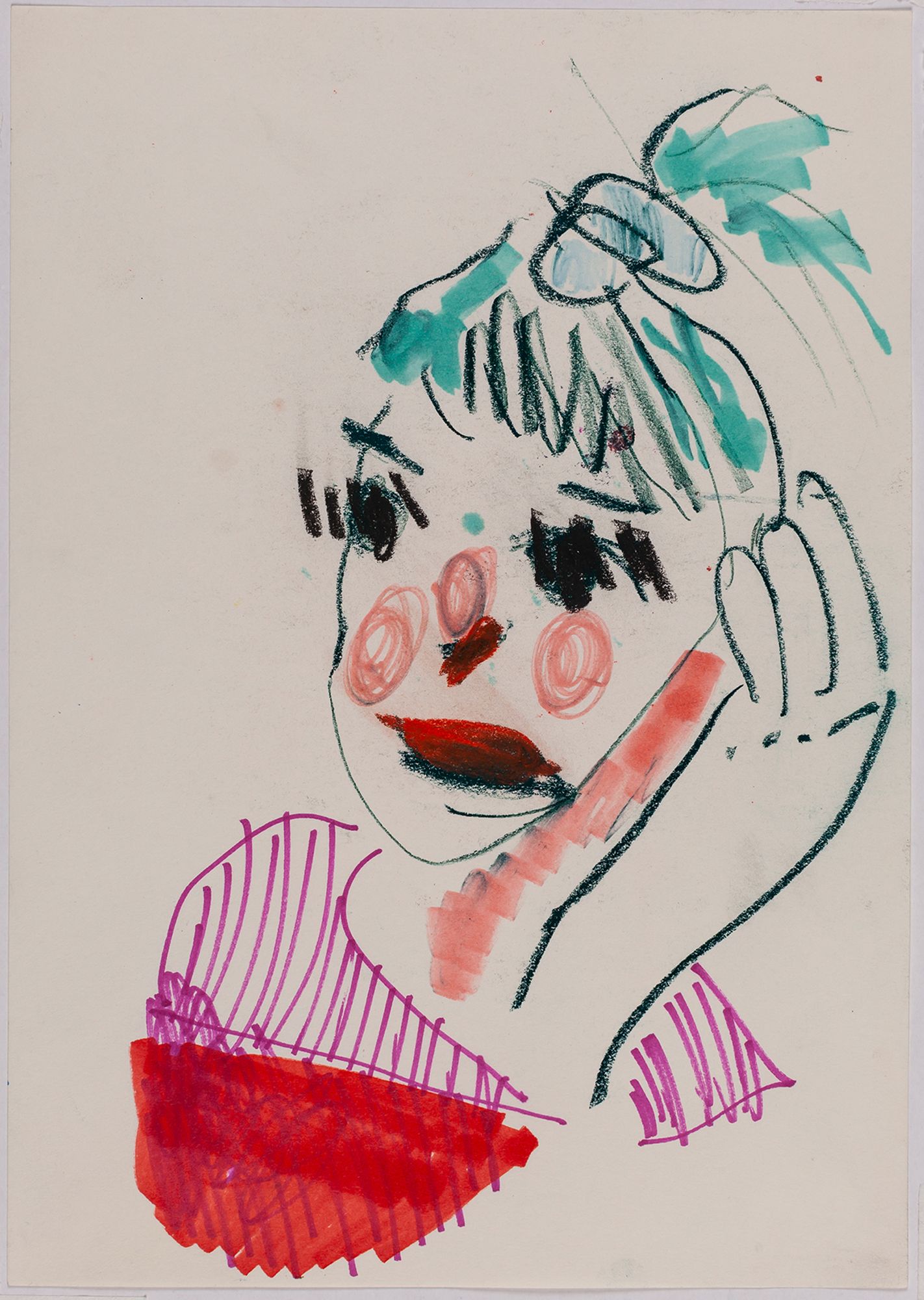

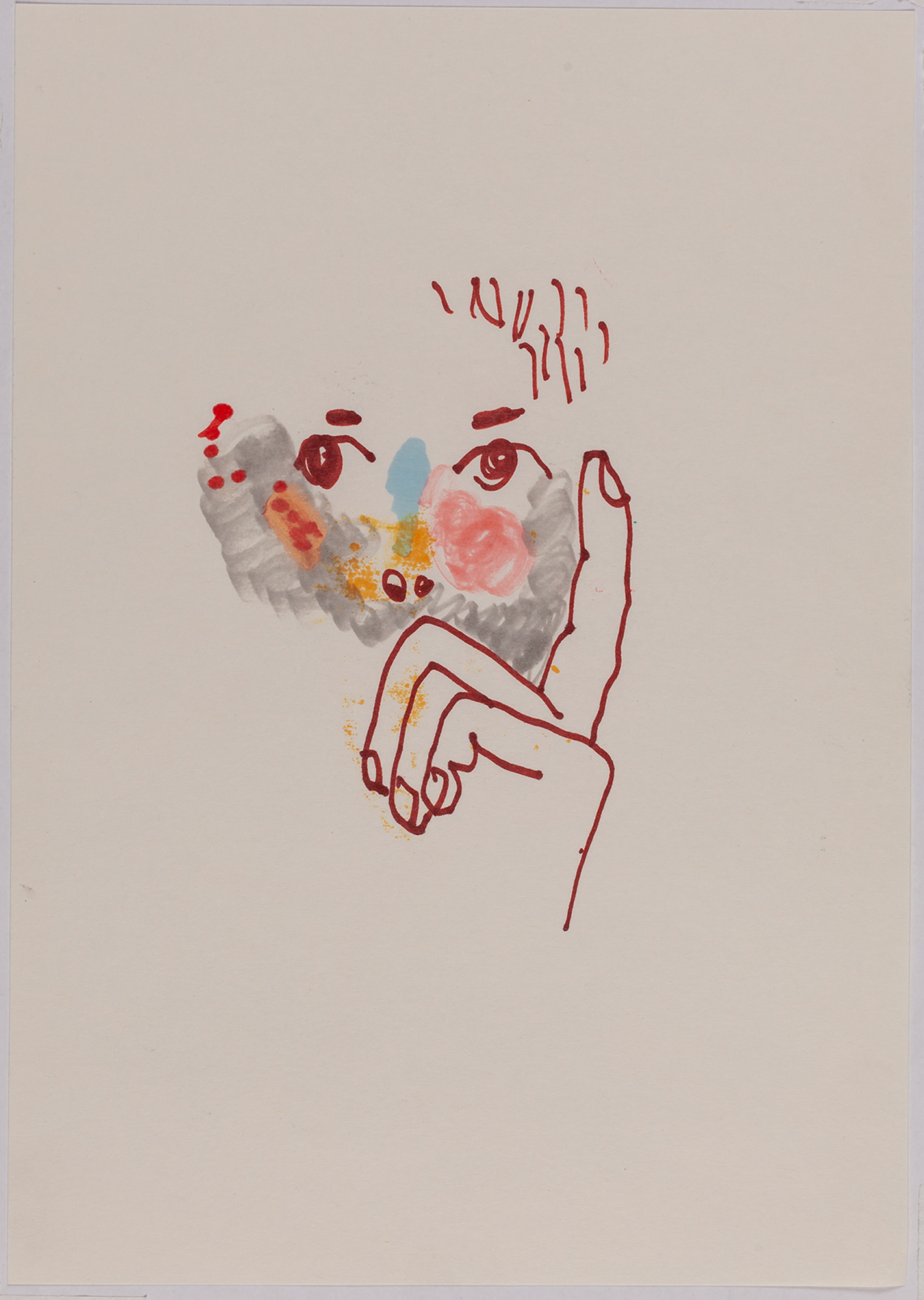

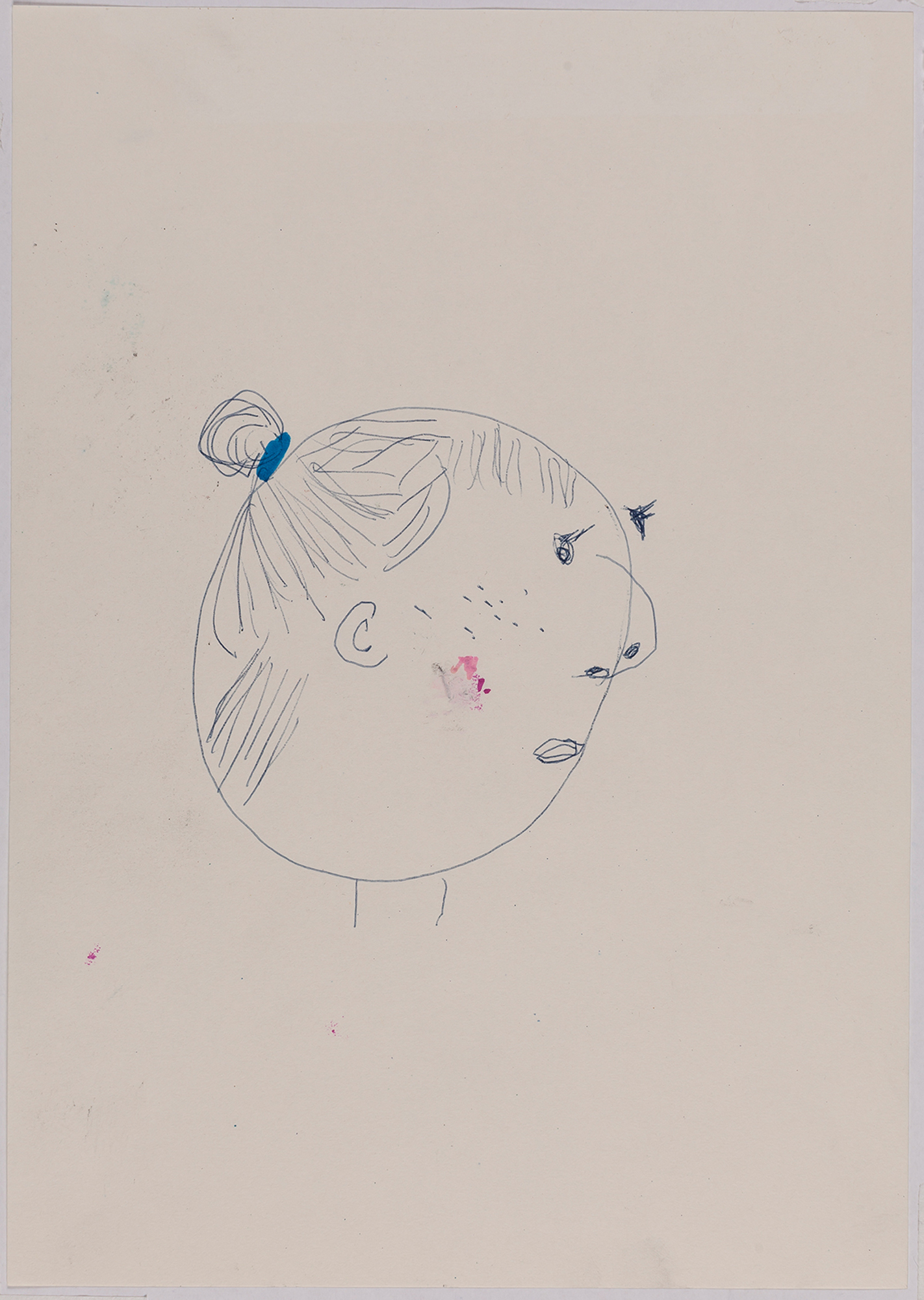

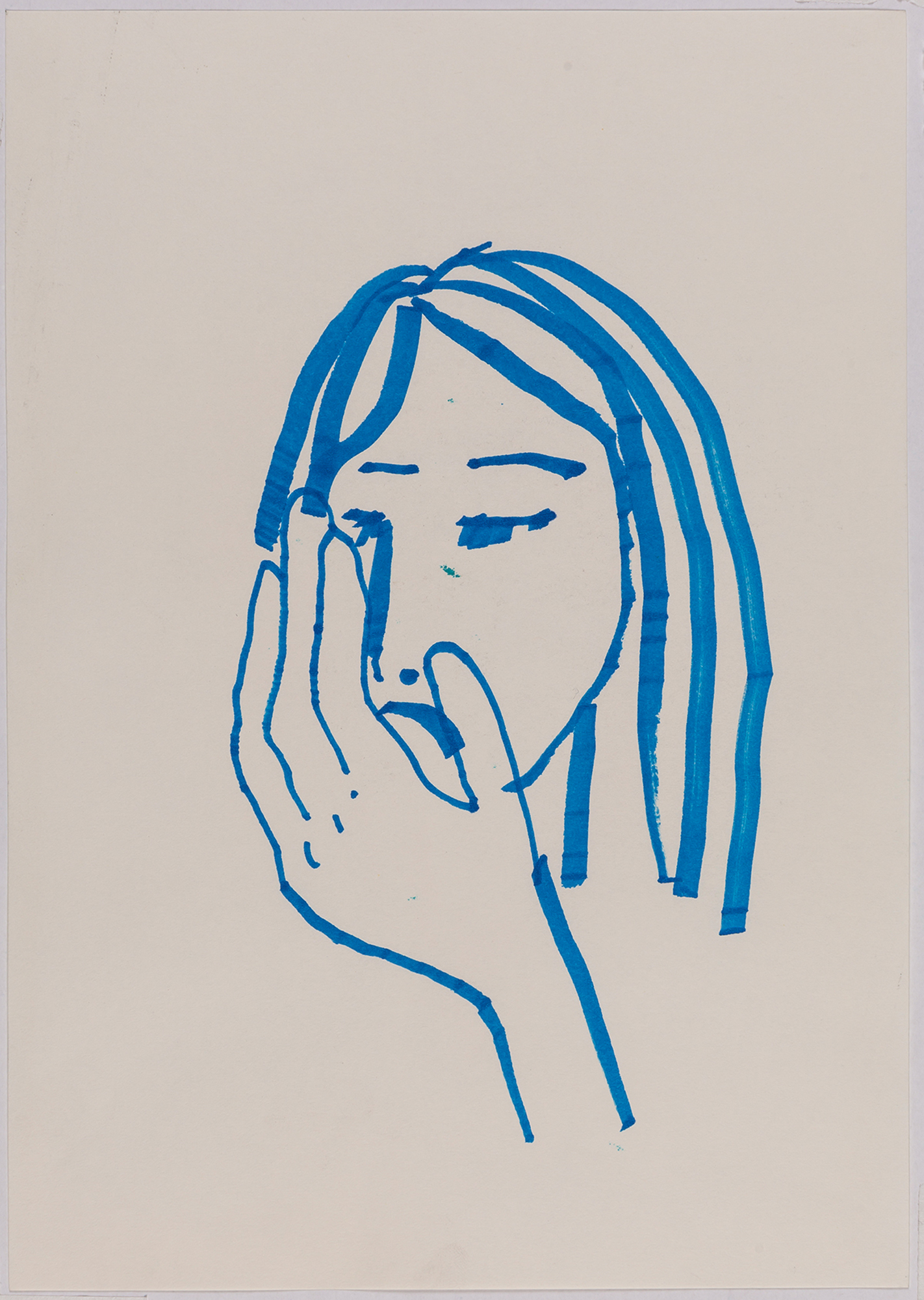

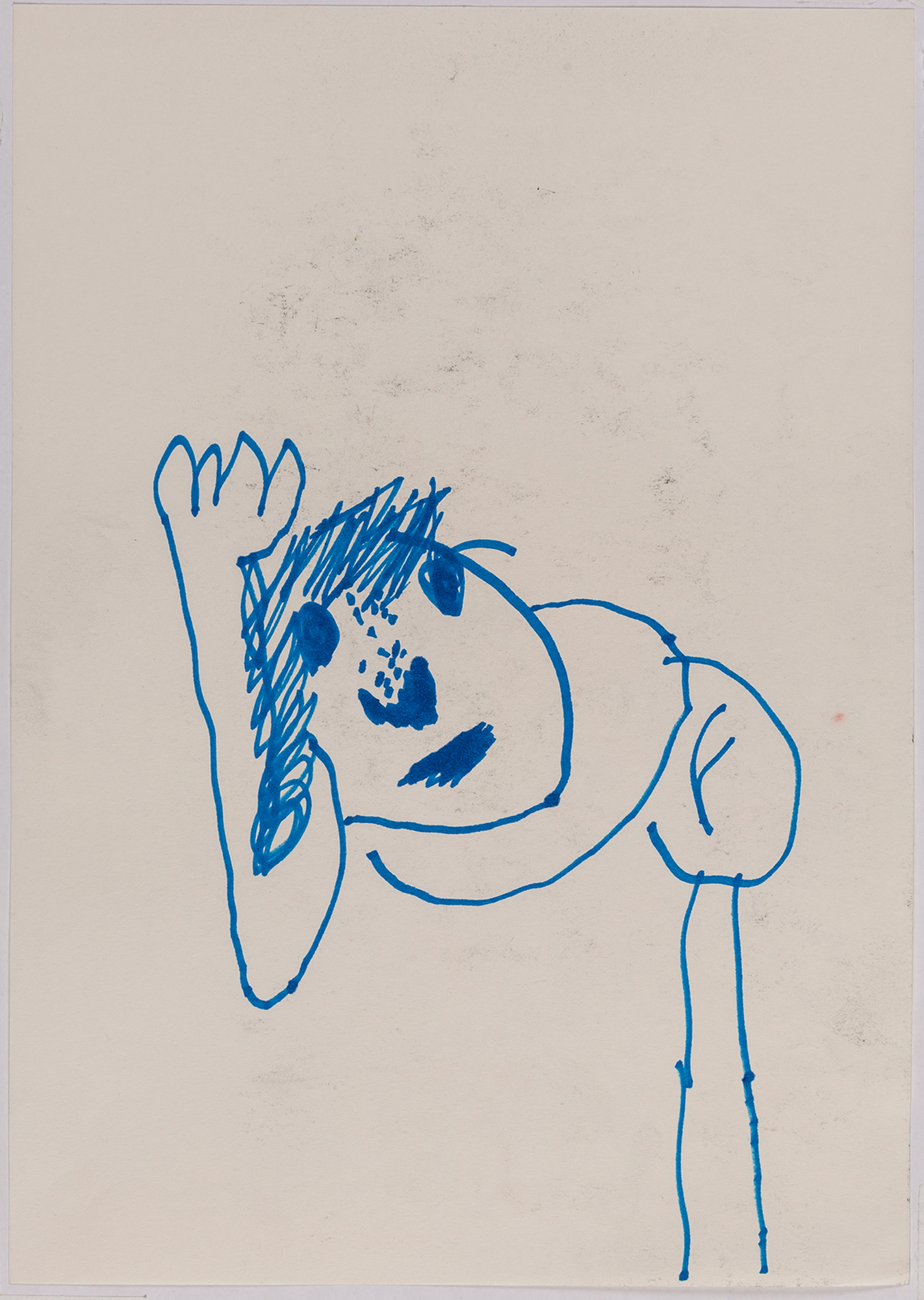

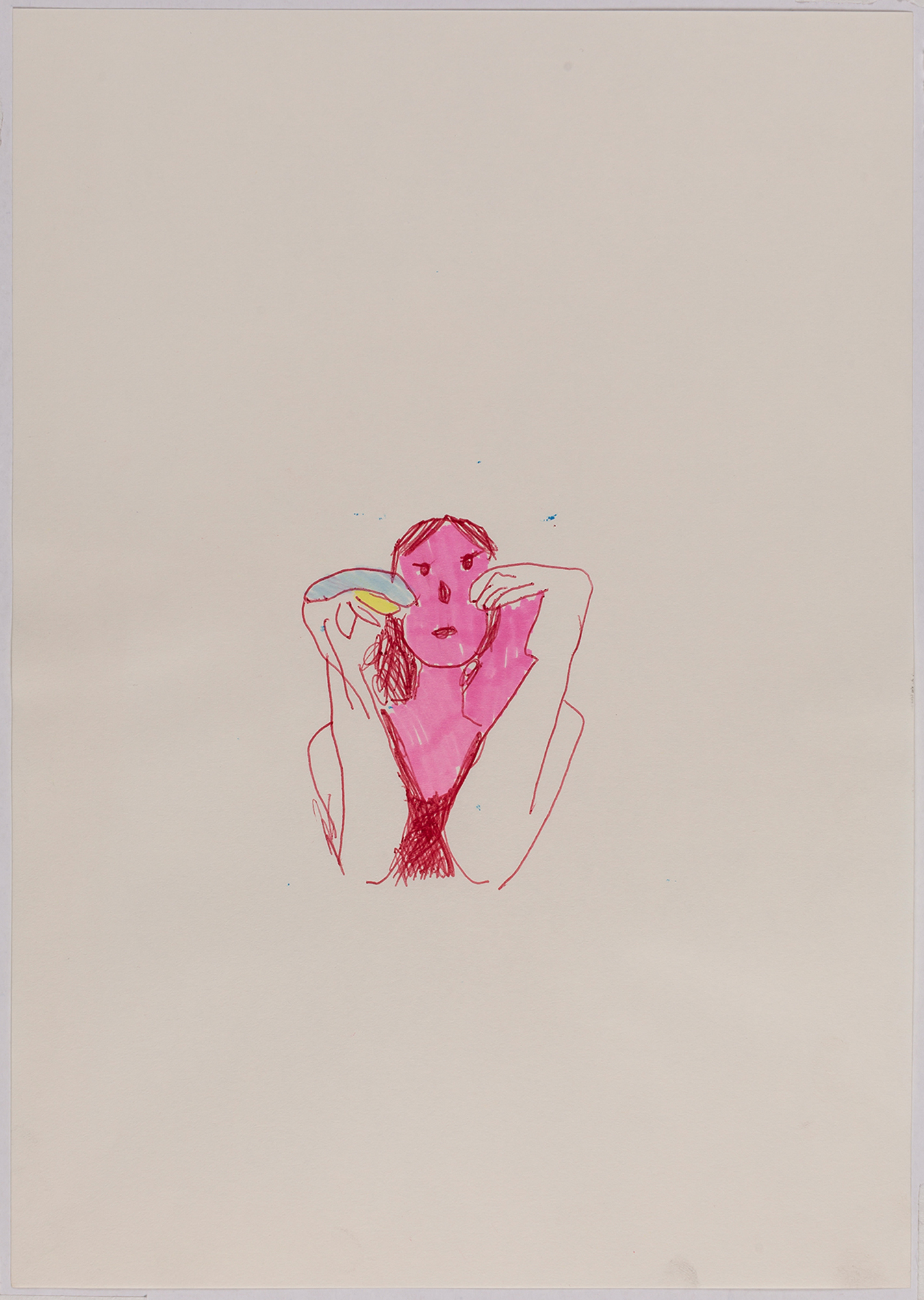

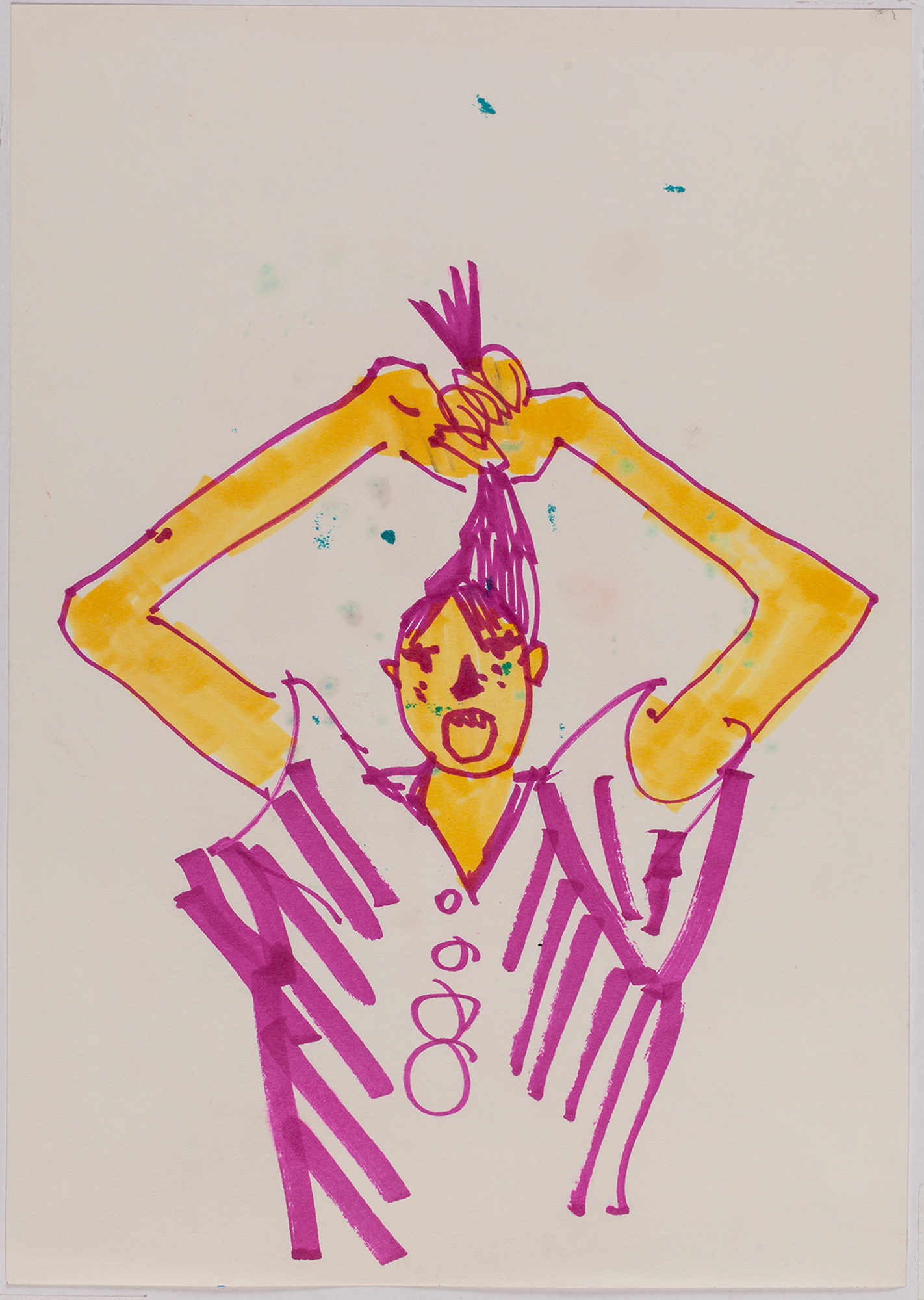

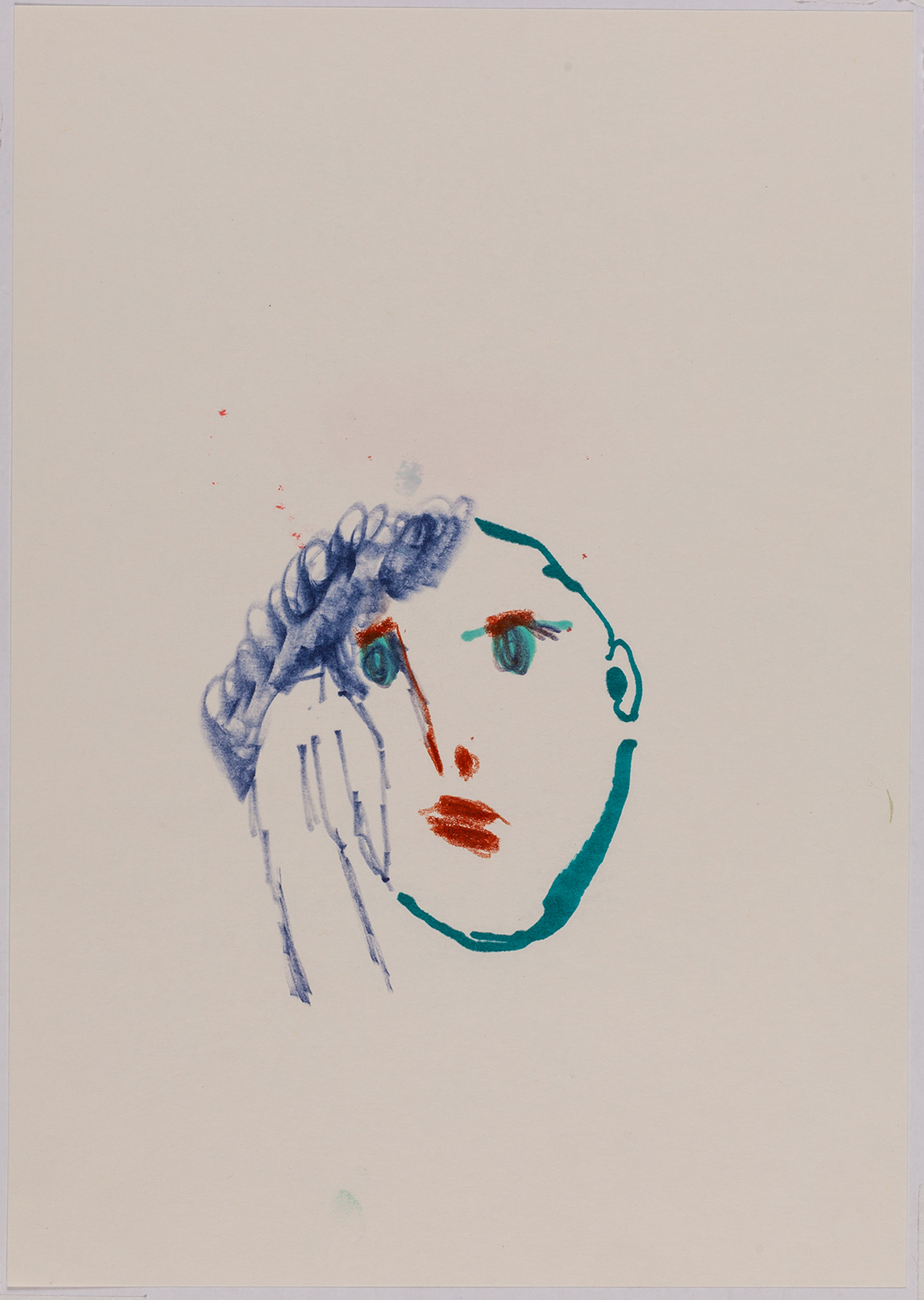

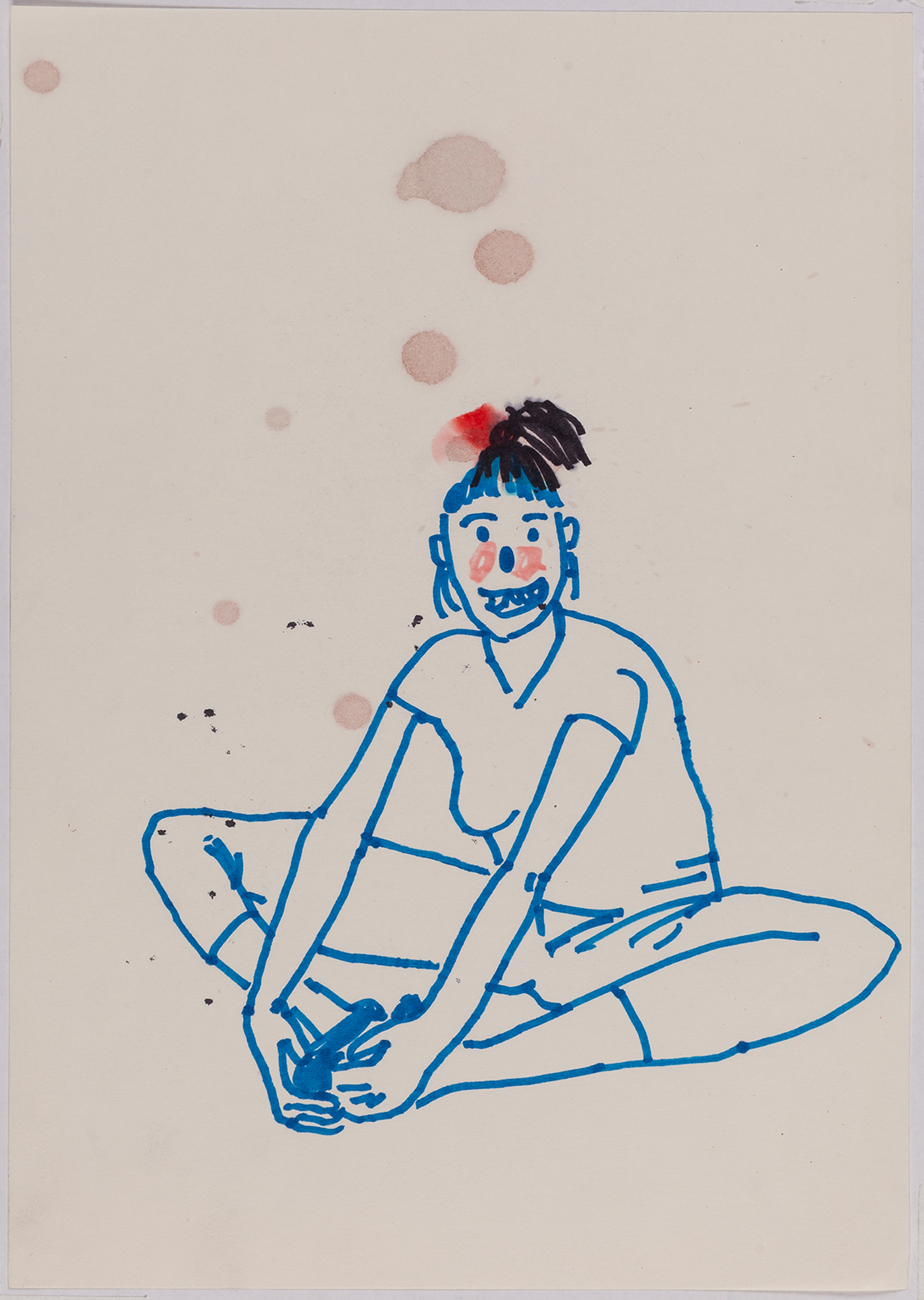

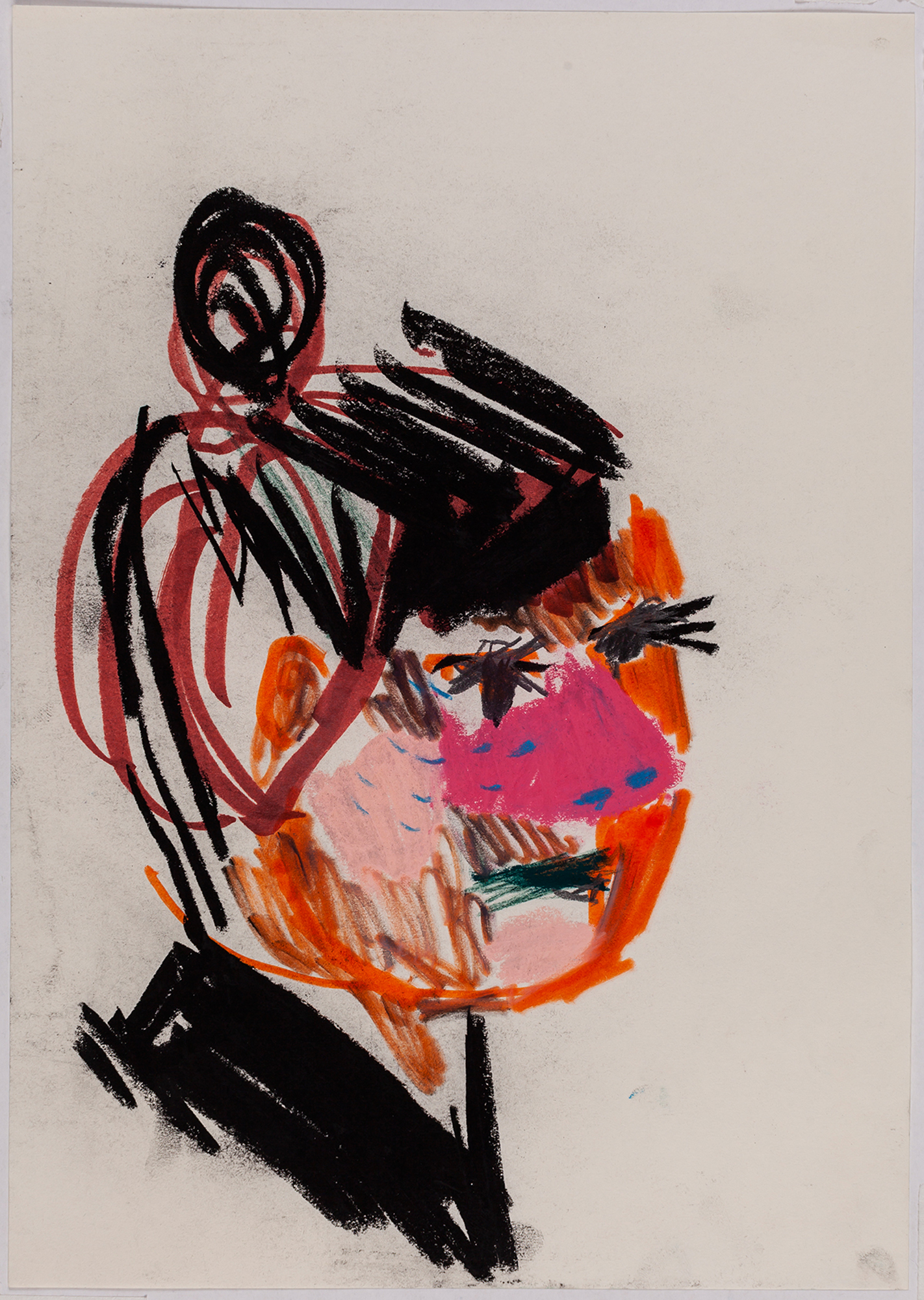

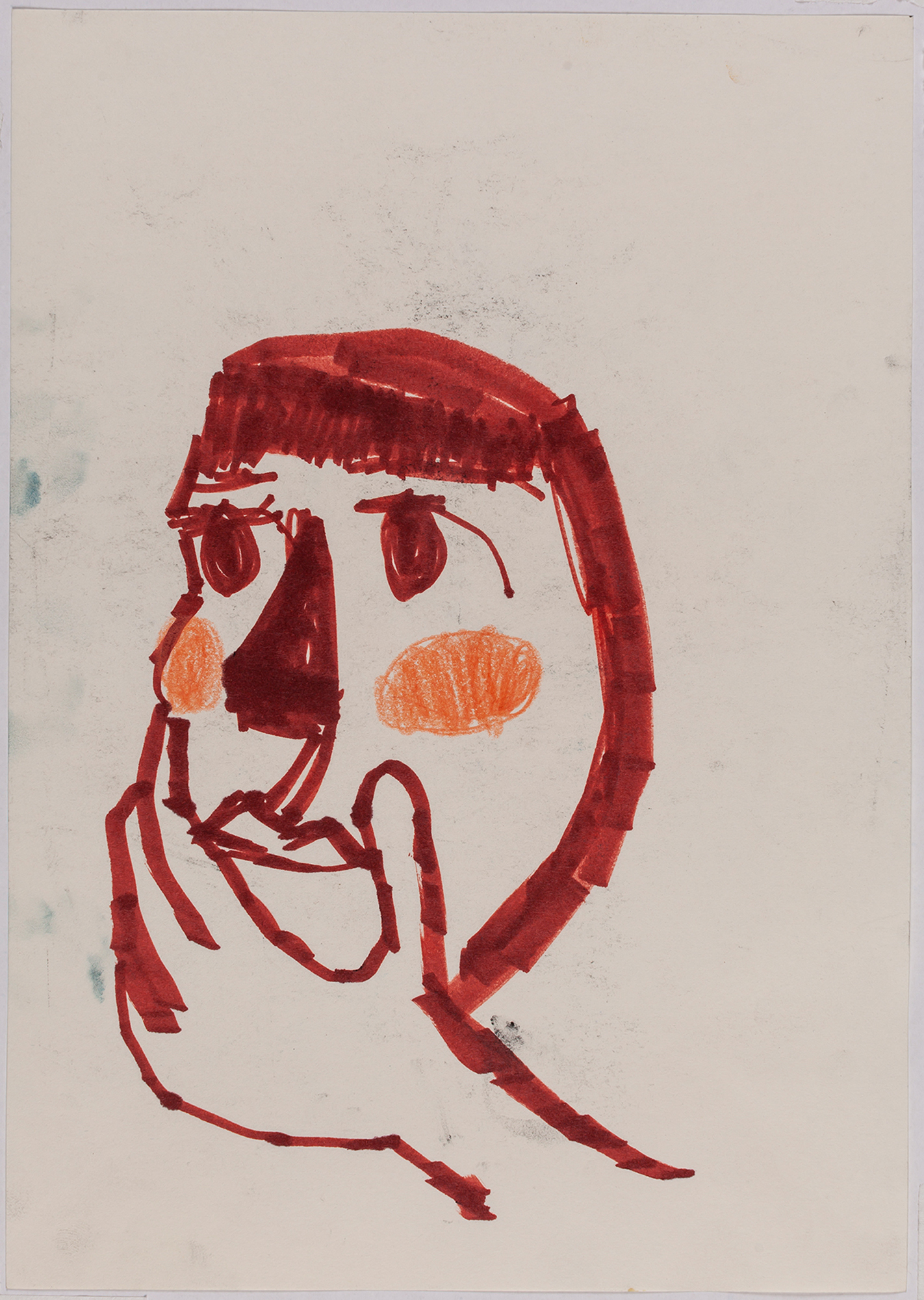

This exhibition by Ana Prata seems to be divided into two sets of works of dimensions and genres very diverse, to some extent even antithetical. However, if we examine the works carefully, what seems contradictory turns out to be much more complex. On the one hand, there are the 33 portraits on paper: small, intimate, always done on white, mainly with a pen, but also with a ballpoint pen, dry pastel, oil pastel, colored pencils, charcoal, and graphite. In this series, titled Portraits of Bia, from 2016, the broad and colorful outline predominates, as if Ana was in a hurry to register the pose of the model in front of her, or as if rehearsing to draw as a child again. More than observation drawings from the same person – Bia, who was an assistant of the artist during that year – are records of domestic and everyday performances, such as raising the arms above the head, supporting the hand on the chin, close the eyes, tie the hair in a high ponytail, and so on. Rather than as an artist and model, the relationship that seems to be established there is that of director and actress of a small theater, as if it was only possible to construct the character through the staging, in the manner of Paula Rego in her work with Lila Nunes, her friend, assistant and model of predilection for decades. With a difference that seems decisive to me: while the relationship between the Portuguese painter and her model extends for decades, which leads to a thickening of the nexus between performance and pictorial representation, the relation between Ana and Bia, to arrive at the type of figuration that we find here, needed a certain lightness – or, more accurately, a certain leggerezza, or lightness. Ana de-dramatizes what, in Paula Rego, would solve itself in the propensity to the tragic.

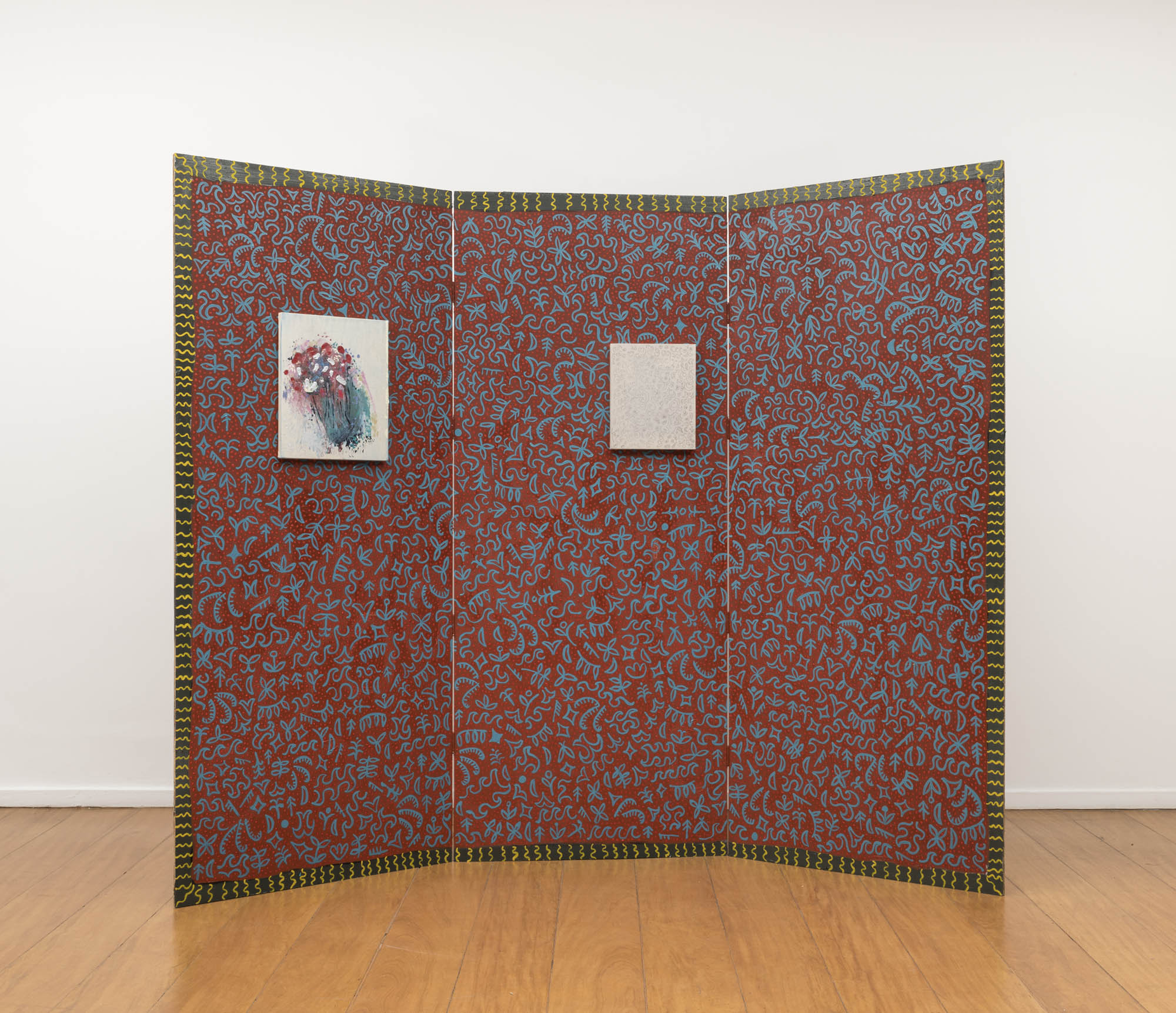

On the other hand, there are two recently made wooden screens: large, imposing, painted with oil and spray. They impose themselves in the exhibition environment, intruding into space. Since they are all composed of three sheets of wood, they could constitute themselves as triptychs – but Ana did not always want to do so. Only one of the screens has a tripartite structure on one of its faces, with a different painting for each of the three divisions, each painting produced from two dominant figures – the triangle for the first leaf, from left to right, and the half-light for the next two-that overlap with monochromatic backgrounds, or almost, in a game of contrasts: red versus pink, black versus gray, green versus blue. The resulting compositions remind us of Volpi, not only by the colors and organization of the geometric forms in space but also by the brushstroke that he does not want to hide. In the other paintings (the other

face of this same screen and the two faces of the other screen), Ana uses the folding structure as if it were a single frame. Two-sided paintings present dissenting paintings, which at first glance seem not to dialogue with one another – which to some extent replicates the tension established in this exhibition between the screens and the portraits. The painting on the back of the screen in which we see the triangles and half-moons organized in a uniform pattern brings a freer, irregular and dirty composition, not respecting contours and purposely keeping the paint drained.

The other screen, on the other hand, contrasts with a pattern that evokes Matisse – not by chance, a book by the artist was on Ana’s desk when I visited her studio – to that which is the most figurative painting of the set of screens, which dialogues with the series of simple boats in aquatic landscapes that is going through the production of the artist, whose main representative is perhaps Boat Trip in the Canal (Paul Klee), 2013, which, as the title well indicates is a rereading of Klee. This painting does not occupy the entire surface as opposed to what occurs on the other face and on the other screen. Centralized in the shape of a trapeze, it has on the central sheet the elements that make it a nocturnal marine landscape: the boat, the strong colors indicating the darkness, a triangle acting as a moon (but at the same time opening the frame to a horizon of abstraction ) and two forms on the bottom, elliptically triangular, which I like to imagine as the fins of big sharks threatening the tranquility of the boatman. When folding the screen, the painting becomes, in the lateral flaps, pure movement of color.

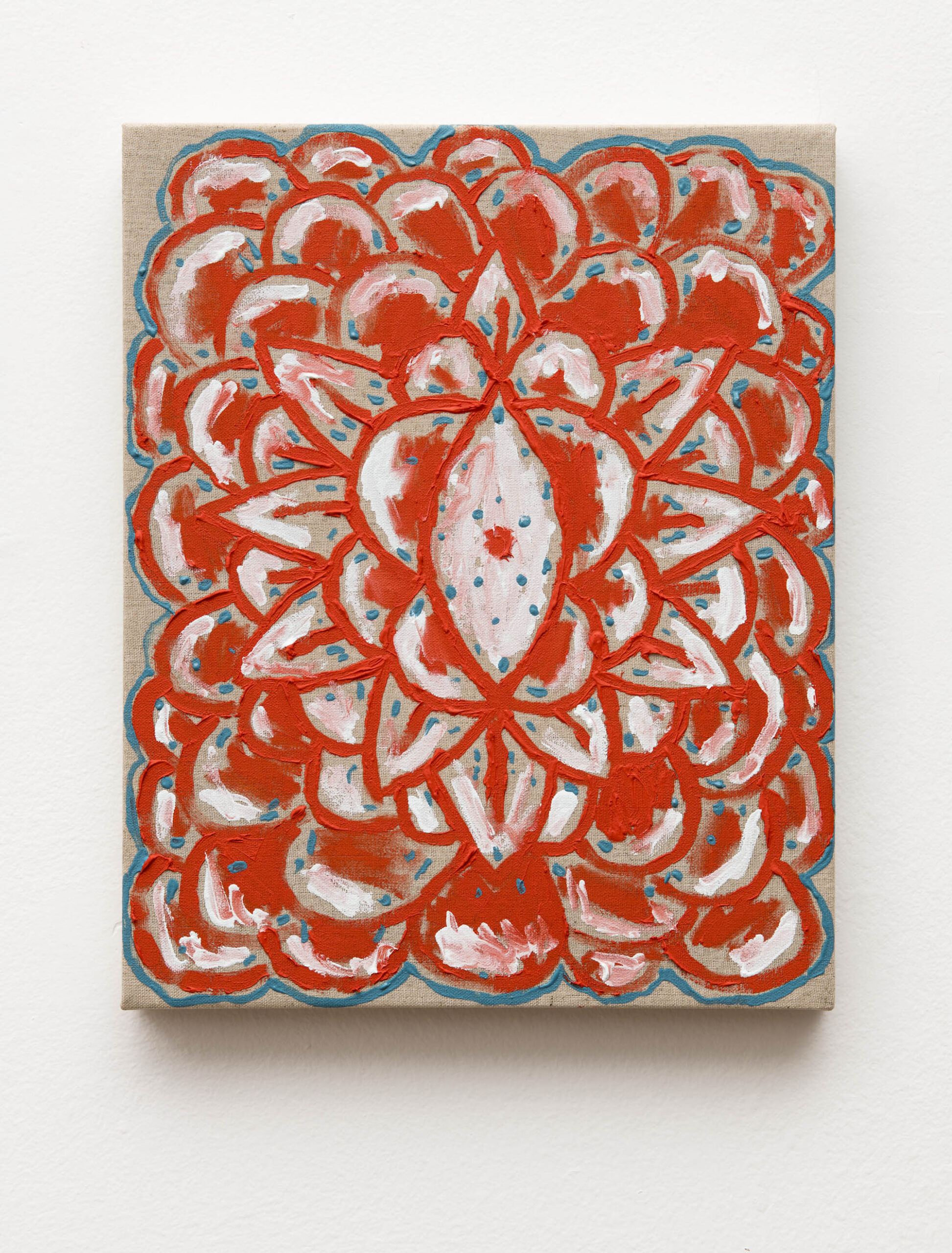

On the screens, Ana arranged small paintings; some with abstract patterns, others with figures, like a bouquet of flowers à la Redon or a wave à la Hokusai. Thus, it also puts the screens to act, assuming the role of support, false wall, a foldable and transportable wall, or a large screen on which not only she paints but also appends other paintings. Not by chance, it is like “folding screen” that the word “biombo” translates into English.

The theater that Ana stages in this exhibition, although starting from a comprehensive and, at the same time, rigorous and inventive rethinking of the tradition of drawing and painting, aspires to the mambembe, when transforming itself at each presentation, when assembling, disassembling and reassembling at her pleasure, by incorporating the elements of the surroundings (sometimes reaching the limit of the readymade) and by pretending simplicity where overflows complexity. It is, therefore, precisely the theater – or, more precisely, the staging – that which seems to connect what at first might seem disparate: the portraits and the folding screens. A theater that lets itself be glimpsed in every detail of the works presented here: in its own processes of constitution (the relation between artist and model), in the dialogue with the great masters (Volpi, Matisse, Klee, etc.) in the overlapping of the small paintings to the screens (making them oscillate between the conditions of autonomous paintings and something like a wallpaper), and even in the mode of exhibition, that is, in the places that the works assume in the space and, consequently, in the interaction with other works. It is a theater in which the roles are never defined precisely or once and for all, they can be rearranged according to the moment.

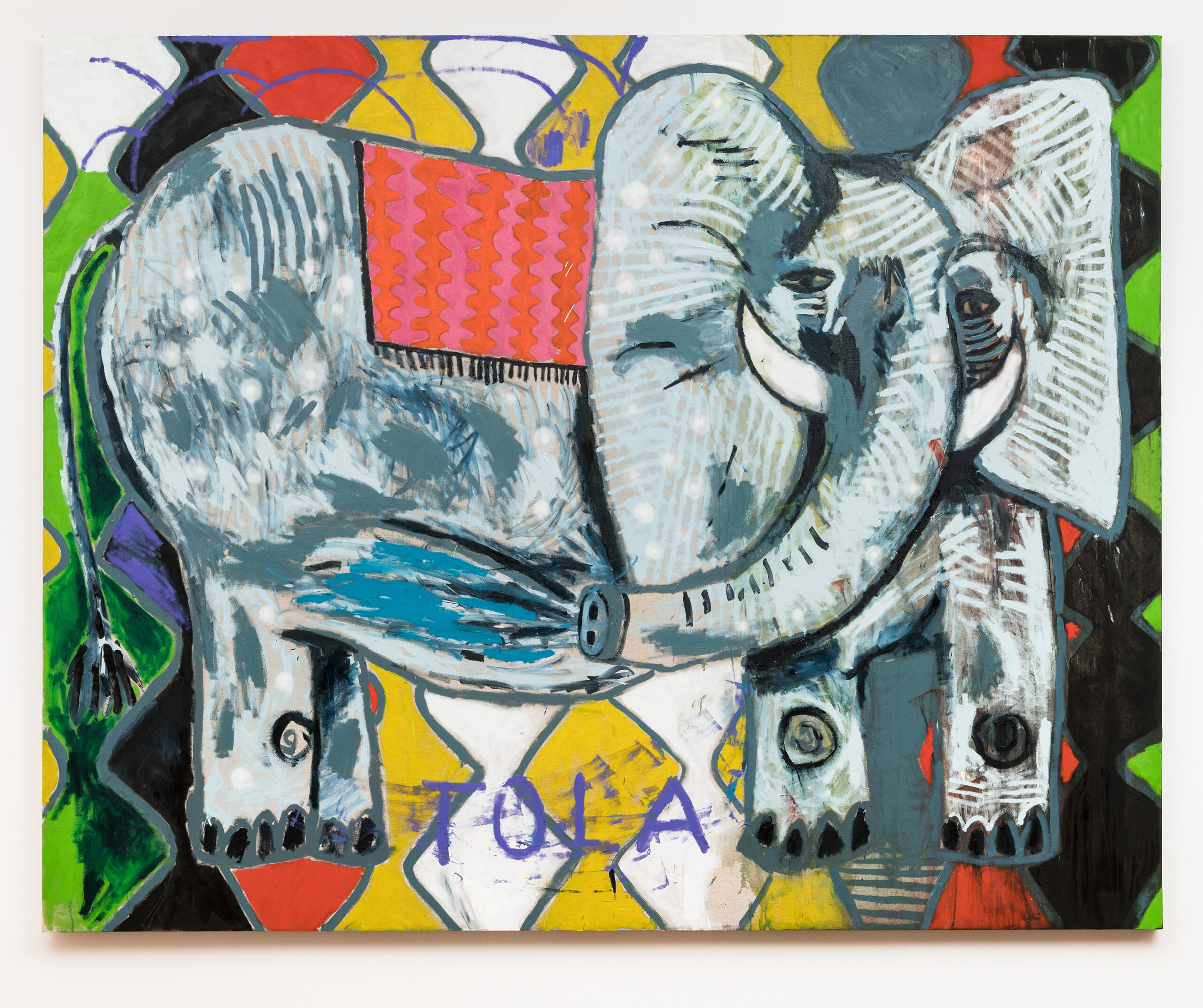

Finally, we can not forget that between one series and another, there is another “portrait”: no longer small and intimate, not drawn on paper, but an immense elephant – the figure par excellence of the circus mambembe – painted on linen even larger than the folding screens. Of all the portraits shown here, it is the only one that appears on a background that is not neutral. The animal hovers over a geometric composition that refers to the patterns found in the circus stalls or in the clothes of the mountebanks so often represented by Picasso. It is an image still gigantic like the screens, but now again two-dimensional – a two-dimensionality that, however, seems to arise precisely from the projection of the painting in three-dimensional structures through the folding screens. This elephant seems to function as an allegorical configuration not only of the tensions that organize this exhibition (the main one being the relationship between screens and portraits, which is, in the last instance, a new way of revisiting the question between figure and background, central to modern and contemporary painting), but also of a procedure dear to Ana Prata, a certain elephantiasis that usually guide the way she deals with the artists with whom she dialogues: by incorporating elements and figures from other people’s works, she almost always enlarges them. This is what happens with the Klee already mentioned, with the Picasso of a folding screen exposed in the Gallery of the Lake of the Palace of the Catete (in Rio de Janeiro) – or even, here, of the folding screens, so to the taste of Matisse: in Prata’s work, they really transform themselves into folding screens. The screens allow us to realize that enlargement is the first step for such elements to take shape – and, detached from the wall, making themselves as walls, in a confusion between being wall or work, come to exist more clearly in space. Prata’s screens are like a fortelling of living beings that the works at once want to be – and know not to be. Situated at the end of this exhibition, the elephant, with its huge body, huge ears and trunk with its own life, seems, not by chance, to be another screen between screens, a folding and pictorial animal, so related to that other elephant , “imposing and fragile,” which Drummond saw disassemble and reassemble itself day after day.